1983, when I was a graduate student in literature, was the heyday of music videos. Among these was Lionel Richie’s “All Night Long” which, to me, was (and still is) exhilarating. A curiously innocuous but satisfying blend of Afro-Cuban-Reggae-Motown-pop-funk, it builds and crescendos to the arc of a street celebration in which the revelers—multi-ethic, multi-generational, and working class—are swept away by the music. What dance! Breakdancing, disco, flamenco, modern dance, kids and adults playing patty-cake, a housepainter doing splits, West African tribal dancers in grass skirts who rebound from the earth as if on springs. Even the two police officers who come to break up the party—one with a billy club in hand—are compelled to dance. The sun rises, the music begins to fade, the party fizzles out, and the remaining revelers vanish into the orange horizon, still dancing.

I told my favorite professor, who was also a music video fan, about my attraction to the video. “That,” she said with disgust, “is just a typical genre of music and imagery that romanticizes the life of the oppressed classes, allowing those of us who oppress them to perversely congratulate ourselves that they are actually somehow better off than we are.”

So much for having a good time.

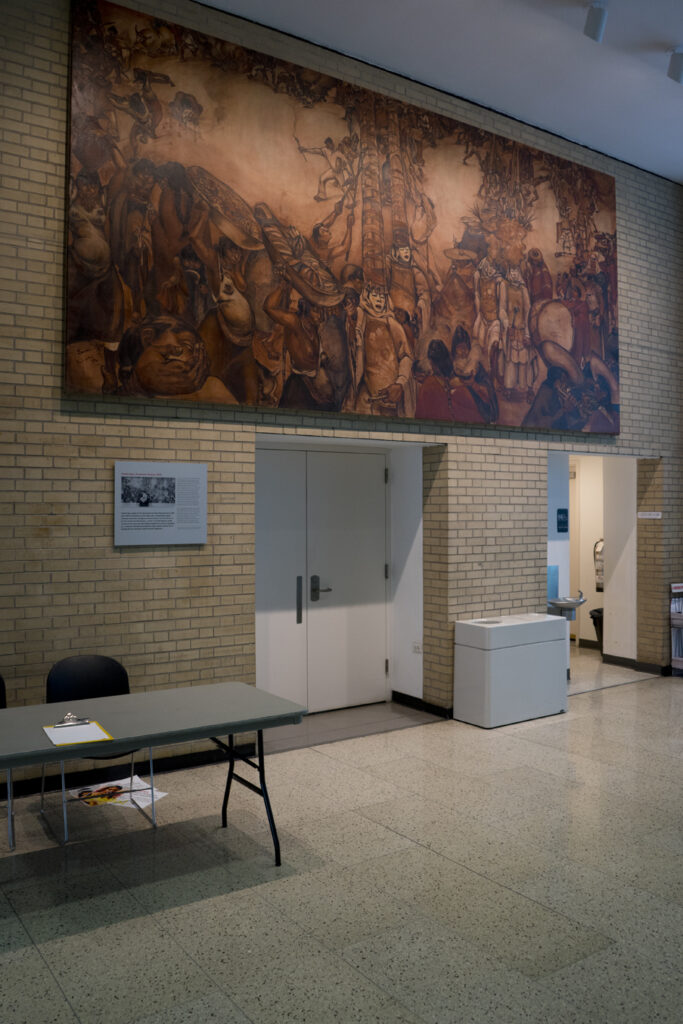

All this came back to me when passing by Camilo Egas’s Ecuadorian Festival for perhaps the hundredth time in the lobby of the building where I work. I finally stopped to read the information posted about it. According to art historian Michele Greet, Alvin Johnson, then Director of the New School for Social Research and commissioner of the work, “described the mural in political terms…” whereas Egas, “described the scene as a celebration or a moment of escape, not as a form of social protest.”

I had always sensed the work had some political relevance, but this had more to do with the painting’s proximity to Orozco’s overtly political mural in the same building, also commissioned by Johnson at the same time. Egas’s mural, with its musicians, the dancers, the giant containers of food and drink, the curving, fleshy bodies, is in sharp contrast to the sculpture-like iconography and earnestness of Orozco’s mural.

Greet points out that Ecuadorian Festival depicts “a celebration that integrates dancers in native costumes from various regions of the country, thereby privileging national unity over regional specificity.” As in the oddly diverse neighborhood of Richie’s video, music and dance in Egas’s work are not merely avenues of escape (which might justify a critique), but powerful forces that transcend social divisions to bring people together. Nothing could be more appropriate for a mural that was to hang in the dance studio—in the basement of 66 W 12th— of this revolutionary institution called The New School for Social Research, which opened its doors to people of all ages and backgrounds who wanted to learn about and practice art and social research.

- Would you favor moving the mural to a place that better connects it to dance, music and the performing arts?

- What would that location be?

- Considering Egas’s vision of music and dance as forces that transcend social boundaries, what kinds of activities can you imagine happening in that space?

Andy Atzert

Staff, The New School