AI think of Haacke as one of the most politically transgressive artists of our time. A master of institutional critique, Haacke has the courage to expose mechanisms of power, control, domination, and hidden interests within the art world and beyond. Haacke’s work presents a challenge to any art collection, as embedded in his work is a powerful critique of the power relations of an institution and of philanthropic patronage—the ways in which art is deployed for the moral upliftment of cultural patrons, the power relations between donors and those whom they fund, and the many conflicts of interest and agenda. Haacke operates in a sophisticated and systematic way.

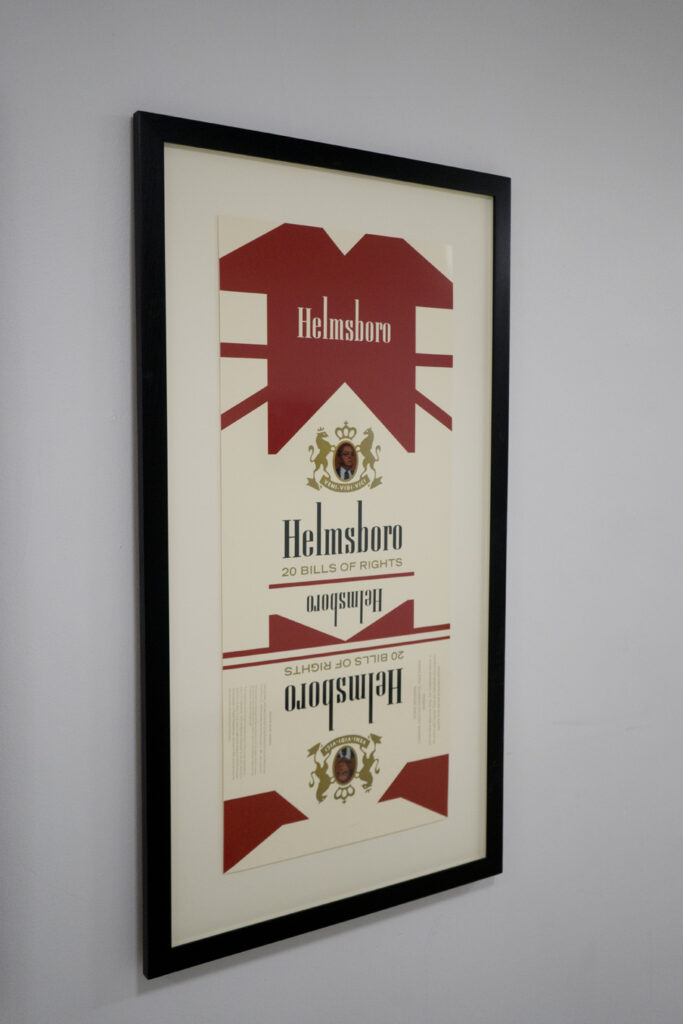

Like a forensic detective, he investigates, scrutinizes, gathers evidence, connects, juxtaposes and finally reveals something surprising and new in the end. In his work, form carries a critical function. In Helmsboro Country, he uses a Marlboro flip-top box to fearlessly attack Jesse Helms (1921–2008), a five-term United States Senator from North Carolina known for his right-wing conservatism, and the tobacco giant Philip Morris, demystifying the relationships and the contradictions between the political, cultural and corporate worlds.

Haacke’s work provides an important key for us as a university determined to reconcile its internal differences and strengths. Haacke is an artist whose main medium is research. Research is not risk-free. It takes time and requires courage and investment in exchange for greater rewards. In this context, the display of our collection has unique opportunities and challenges. Categories such as “Conceptual Art”, under which Haacke’s Helmsboro Country is currently displayed, is informative and educational but intellectually limiting.

How might we take our lead from Haacke’s investigative approach to create the possibility to connect with the university collection in a deeper way—to openly discuss our own differences and strengths? How might we challenge and subvert the mechanisms of representation—by adding other clues to an art work, perhaps?

How can we create mechanisms of engagement with art that are more dialogic and agonistic? What strategies could we explore that would go beyond classification to foster more unstable and challenging relationships with the work?

Can the technologies with which we teach and conduct research be used to nurture conflicting but also more meaningful associations?

Eduardo Staszowski

Faculty, Parsons The New School for Design