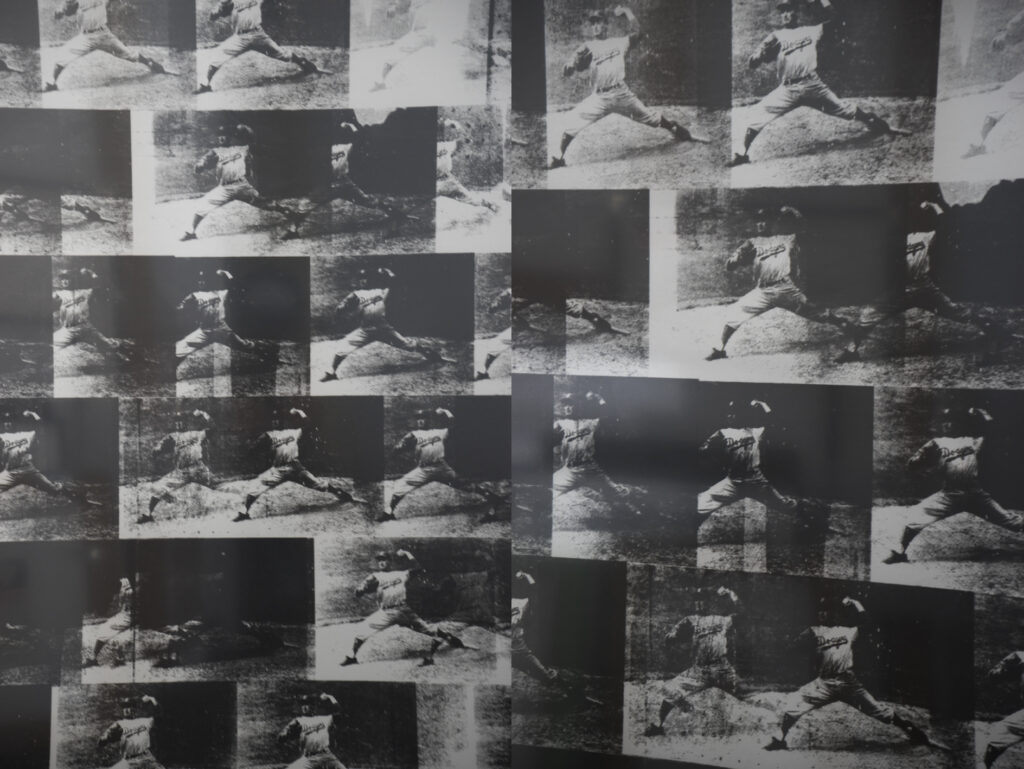

When it still hung there, I would draw a surprisingly high level of energy from Deborah Kass’s piece, Baseball (Sandy Koufax), during faculty meetings, performances, and other events in Wollman Hall. The screen print was like a friend or companion. Kass’s Warhol-style tribute to Koufax the icon celebrates the southpaw’s symbolic position among American Jews, whose perfect delivery was itself a kind of artistic masterpiece. I admit I’m embarrassed and conflicted about my love for Koufax because it’s such a cliché, but I can’t deny the overwhelming sense of joy every time I see that image. Even now, writing this essay, I’m smiling thinking about Koufax and his jaw-dropping scorecard, the organizing principle of Jane Leavy’s brilliant biography, Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy. I often wondered if others felt anything similar in the meetings. Did my non-Jewish colleagues feel anything at all when looking at Koufax and Kass? It’s hard for me to imagine. Who else even recognized him? Did they stop to think about this piece, or why it might be placed among the other deep and powerful pieces in Wollman, as I did?

I adore Deborah Kass’s work because it engages the complicated feelings of belonging, joy, pleasure, humor, pride, and mystery that accompany “race” and “ethnicity.” These two deeply problematic terms certainly require rigorous critique, yet we do ourselves a disservice if we engage race and ethnicity joylessly and without humor, or only address them when we take offense. (Even “offense” is an attractive aesthetic experience for many—ask anyone involved with punk, hip hop, or stand-up comedy—as is violence—take boxing, football, hockey, the moshpit.) These terms and experiences are not restricted just to “Jews” or racially and ethnically marked groups, since race and ethnicity are fundamental to the arts, including sports, through which we express ourselves in our social lives. With that in mind, I think it’s important to take seriously the aesthetic and stylistic components of race and ethnicity in the broadest possible ways.

How do we bring in the joys and pleasures of race and ethnicity as part of a social critique?

How can such a stylistically or aesthetically informed social critique serve a social justice agenda rather than a reactionary ideology or an exclusive “us vs. them” mentality?

How can we include the deep aesthetic experiences of “diversity” for all members of a society, without creating or reinforcing a hierarchy: i.e., that some experiences are deeper or more meaningful than others, simply by virtue of a particular group affiliation?

Evan Rapport

Faculty, Eugene Lang College The New School for Liberal Arts