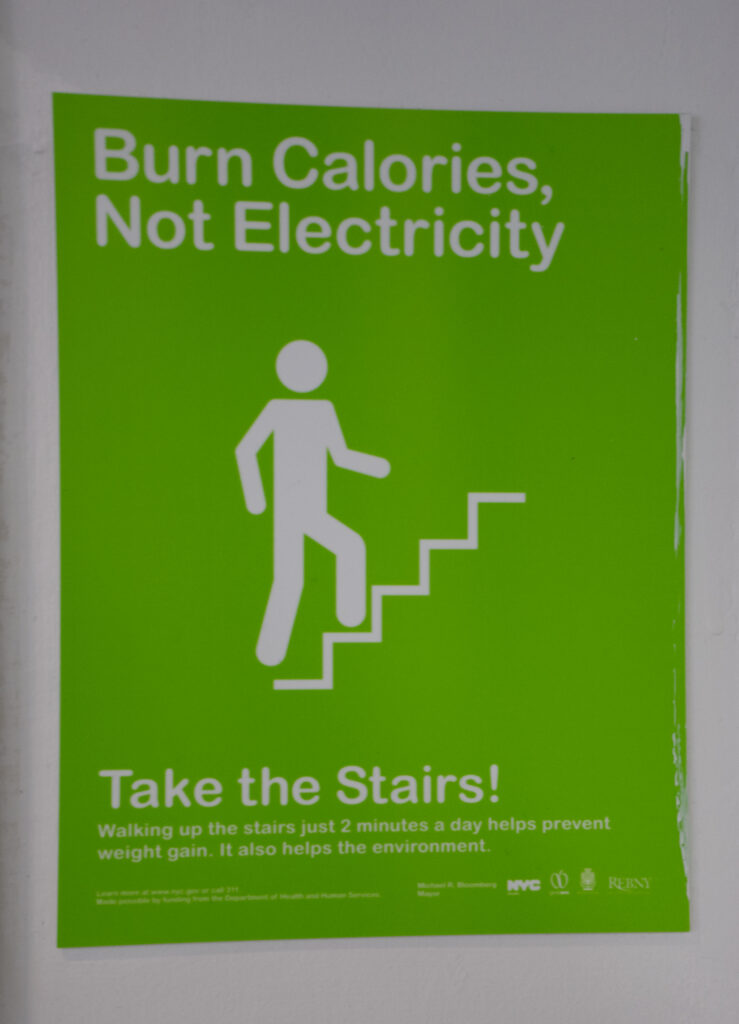

A “Burn Calories, not Electricity” sign hangs at nearly every elevator bank within The New School’s buildings, encouraging people to take the stairs. Though the basic suggestion is apt, given the high demand for University elevators, the visual and political strategies used are biased and potentially alienating. To be clear, I see nothing wrong with a sign that thoughtfully suggests that people use the stairs for the sake of convenience—if they are able and want to do so. However, here, the benefit of stair use is defined as preventing personal weight gain, linked further to the ecologically friendly act of utilizing less electricity, tacitly stigmatizing elevator users as lazy, fat, and wasteful— especially alienating people with mobility issues and/or “extra” pounds, whose physical presence and choice to take the elevator become subject to particular scrutiny and judgment.

As a person of size, I experience the socially marginalizing nature of the signs first-hand; as a faculty member I find its design and content in conflict with my teaching objectives and The New School’s stated “mission of challenging the status quo.” Capitalizing on many of the same visual strategies that we teach our students to deconstruct in the classroom—using Helvetica to elicit the transparency, objectivity, and authority that this font suggests, combined with a seemingly universal symbol sign and a cheery “eco” green—the ubiquity and seeming permanence of the signs, suggest that The New School officially discourages fatness. The uncritical bias of this message actively contradicts the rigorous work being done at The New School on “obesity” as a social construct as well as the numerous faculty, staff, and student-led initiatives that strive to create an inclusive University environment and promote body positivity.

The sign is actually part of a city-sponsored public health campaign that former Mayor Bloomberg piloted at Parsons, debuted by him at a press conference in the lobby of The Sheila C. Johnson Design Center last July—when student and faculty presence is particularly low. Discussed in terms of “active design,” the sign was linked to the University Center, a green building with prominent staircases that is the new face of The New School. Exploring design solutions to social problems becomes a dubious enterprise when the definition of, and solution to, these problems further disenfranchise marginalized groups. There is a disjuncture between the University creating new spaces that invite dynamic, inclusive uses and designing an environment that shames people should they seemingly transgress by gaining weight. Though we may not be aware of it, through these signs, the University is actively participating in the city government’s anti-obesity campaign;, these little green signs communicate the same values as other city-sponsored anti-obesity ads that aggressively dehumanize fat individuals (including children) by depicting them as pathologized cautionary tales.

Are there ways to promote “active design” without alienating people?

How can we, as designers and educators, foreground systemic inequities—food production/distribution, healthcare, among others—with the same graphic urgency that is often reserved for individual responsibility/blame?

Does The New School have an obligation to inform its students, faculty, and staff when it adopts signage/values that originate from outside the university?

Leah Sweet

Faculty, Parsons The New School for Design