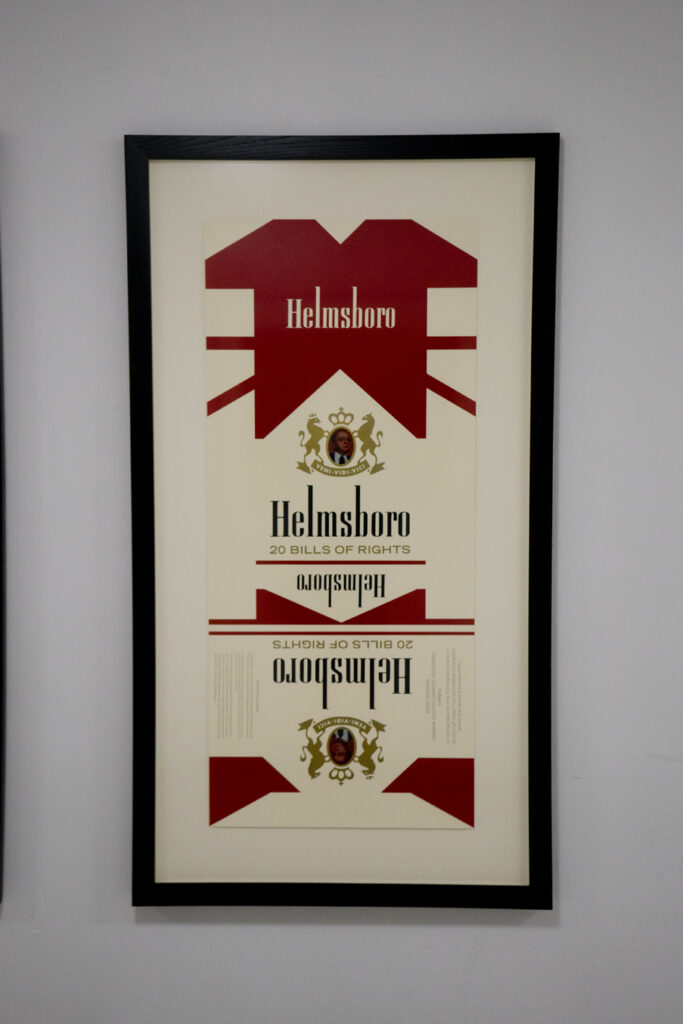

I have worked at The New School for over twenty-five years. An art work from the University Collection that has always evoked strong feelings is Hans Haacke’s Helmsboro Country. I have come upon this work often over the years and it has captured my attention every time. It seemed to be in a class by itself, although it was labeled conceptual art at the time.

Although I am an abstract painter, I have followed politics since I was a teenager.The work is politically specific and layered, and contrasts corporate-political manipulation (Philip Morris Corp. & North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms) vs. American political ideals (The Bill of Rights). At the time, this piece referred specifically to Sen. Helm’s attack on the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) for paying $30,000 for Robert Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic photos. Helmsboro County raises the question: How can Sen. Jesse Helms serve two masters—the U.S. government and Philip Morris Corp (i.e. corporate America). While the NEA controversy from 1989-’91 is long past, I still wonder what has happened to this kind of political sophistication resulting from one artist’s research of political and cultural systems?

Haacke is a visual artist provocateur—more of a political activist than a humanitarian. I grew up believing that artists were uniquely perceptive about what is going on around them. With Haacke, I found an artist who is more analytical than perceptive. His is a critical voice that exposes the damage to democracy created by the collaboration between corporations and politics. It is difficult not to appreciate the moral courage in his work. I respect its honesty because speaking truth to power always carries some risk. Haacke is also a sophisticated communicator, past master at identifying complex conditions and transforming them into elemental visual signs for all to understand at a glance.

What can work like this teach us, as artists and designers, about understanding the cultural systems in which we are embedded?

When a work like Helmsboro Country hangs in NYC (the cathedral of capitalism) can it really function as a critique, exposing conflicting American values?

Is the tension between individuals and institutions that this painting exposes found in all institutions, including our own university? What can creative individuals do about it?

Michael Palumbo

Staff, Parsons The New School for Design