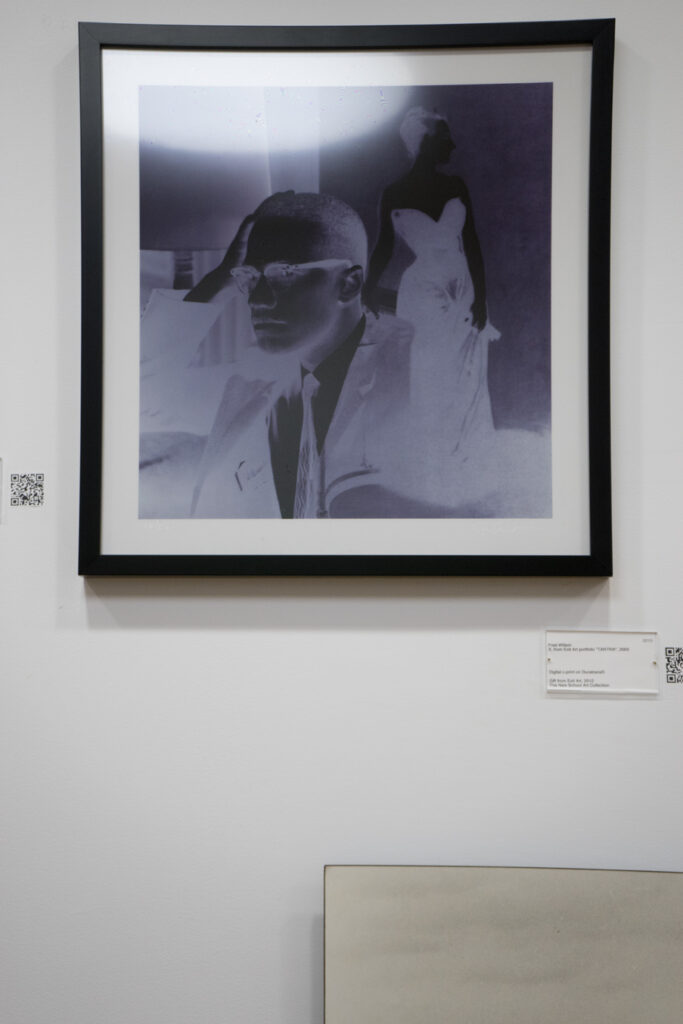

In X (2005), Fred Wilson juxtaposes the images of John Singer Sargent’s scandalous bourgeoise Madame X with the political activist, Malcolm X. Wilson is well known as an art provocateur committed to creating art that provokes discomfort in the viewer. Each time I step off the elevator across from it, X grabs my attention. I am reminded of the turbulent 1960s and Malcolm X’s aggressive political activism and struggles against the oppressive systems of racial and economic inequality. His image, poignantly staring beyond the frame with unseeing eyes, compels my own gaze—the historical gaze of an African American woman trying to deconstruct the issues of race, gender, inequality, and injustice still so prevalent today. Being relegated to a small frame, in close proximity to the seductive Madame X, disassociates Malcolm X from his iconic context. Yet, the proximity also provokes a not-too-subtle subtext about the underpinnings of systemic and institutional biases. X is at once incredulous, incongruous, perplexing, and unsettling. And despite the intentionality of the artist, or perhaps because of it, Malcolm X’s image within the composition has been stripped of its symbolic revolutionary skin.

But this “stripping” of Malcolm X is not the first in The New School’s history. Since its founding in 1919, this institution has publicly promoted itself as a progressive institution, defender of the right to free speech and freedom of expression. This was evident when in 1963 The New School planned a series of public lectures entitled the American Race Crisis, scheduled to take place in Spring 1964, in response to the spiraling racial tensions spreading across the country. The invited speakers included distinguished African Americans leaders: the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., James Baldwin, Ossie Davis, John Killens, and Malcolm X. At that time Malcolm X was a minister in the Nation of Islam and known for his fierce rhetoric, activism, and inflammatory speeches. A bold move indeed on the University’s part.

However, between October and December of 1963, the invitation was rescinded because of Malcolm X’s now infamous remark, “the chickens have come home to roost,” in response to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. In this instance, the institution failed to uphold its own principles of ‘a “new school” willing to take intellectual and political risks.’ Dean William Birnbaum conveyed the sentiments of the university’s leadership to Malcolm X: “Your personal conduct has not been in keeping with the traditions and decencies honored at The New School. You are now not invited to speak at The New School during the Spring Semester 1964 or at any other time.”

It is ironic that the “Disinvited Guest” is now a permanent presence in The New School’s art collection. Students, staff, faculty, and members of the public encounter his image on a daily basis.

Was the work purchased or donated knowing Malcolm X’s history at The New School? What does his image now invite us to ponder about inequalities, injustice, rights and race in our own institution and in the country?

Would Malcolm X be surprised to see his image hanging on the walls of an institution that disinvited him?

If Malcolm X were alive today and made the same infamous remarks in connection to 9/11, would he have been invited to speak at The New School during any of the public lectures that were held on campus?

Thelma Armstrong

Staff, The New School for Public Engagement