January 1931

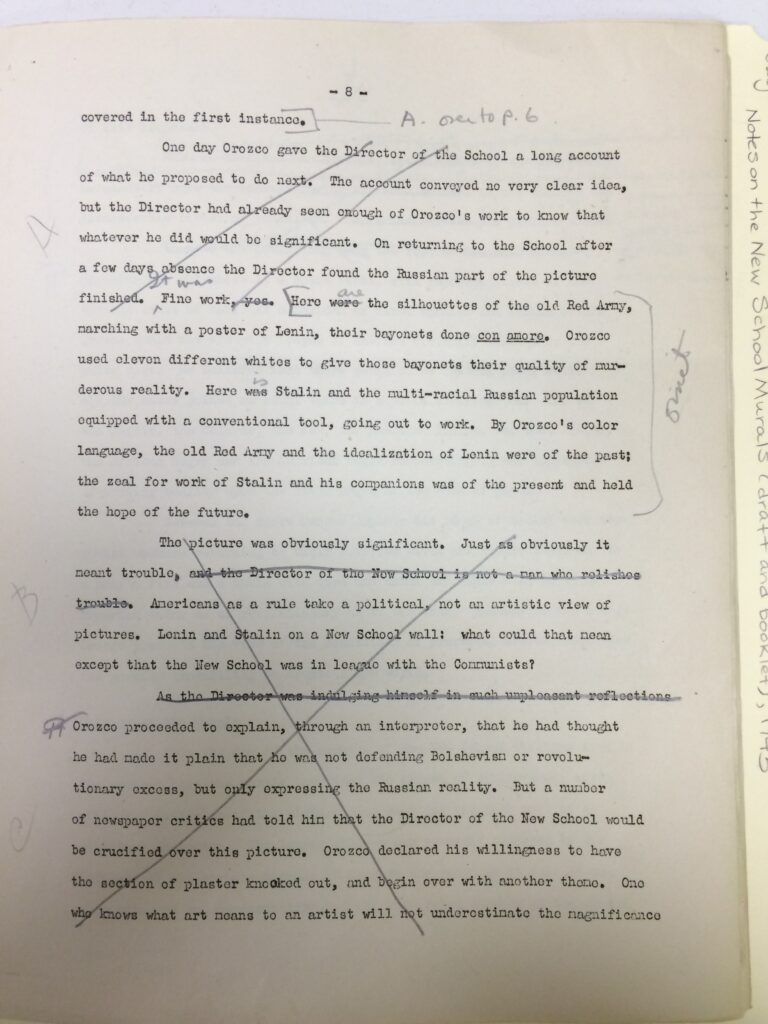

The New School moves into 66 W. 12th Street, a building designed by Joseph Urban. Murals by José Clemente Orozco and Thomas Hart Benton are unveiled.

1946

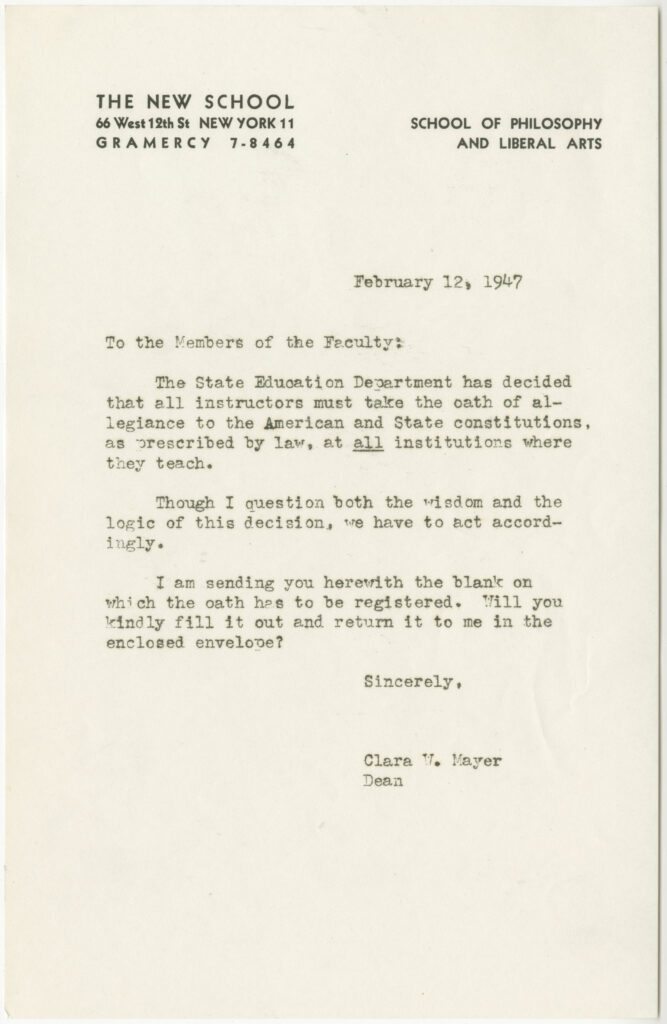

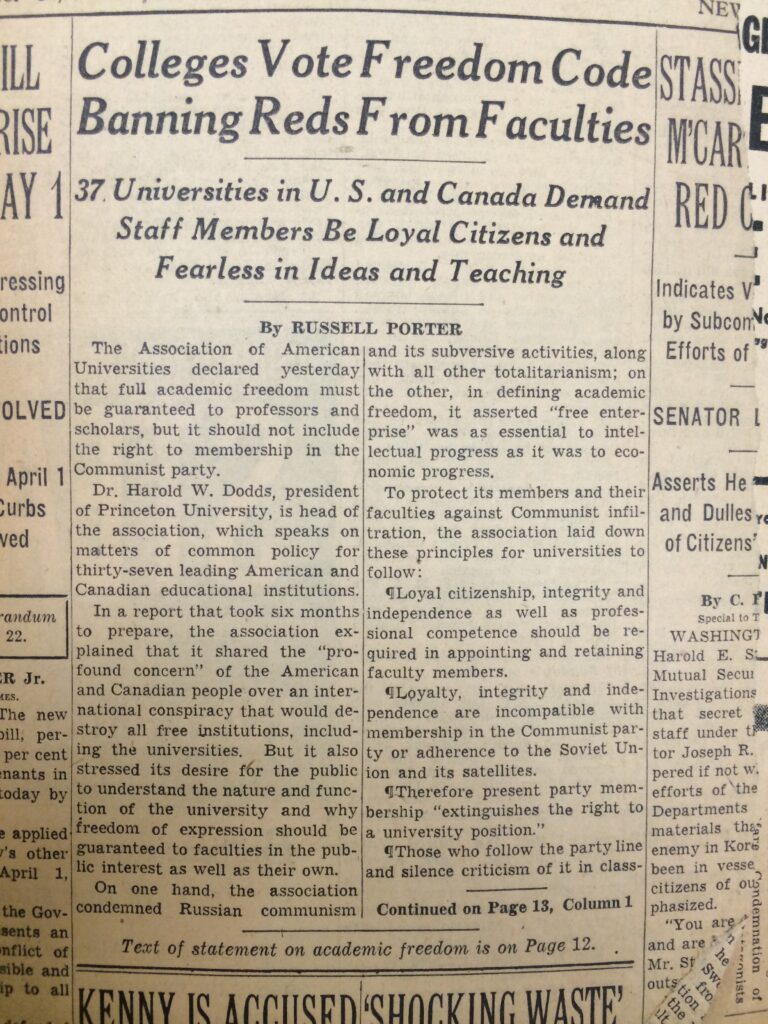

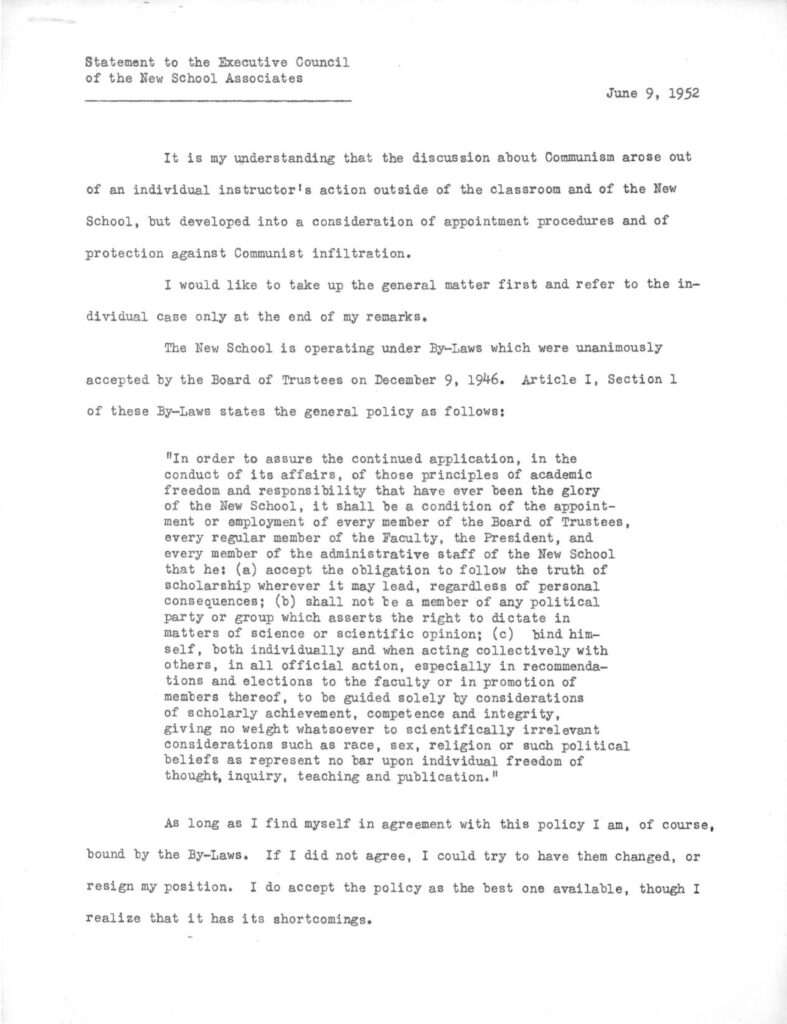

Academic freedom is a valorized principle of The New School, which was founded in opposition to universities rife with administrative power and bureaucracy. Realities soon war with ideals in the early years of the school, bringing both administrative structure and more rules. In the chill of the post-World War II world, the administration revises the school’s by-laws. In addition to accepting “the obligation to follow the truth of scholarship wherever it may lead, regardless of personal consequences,” every person employed by the New School community shall not be “a member of any political party or group which asserts the right to dictate in matters of science or scientific opinion.”

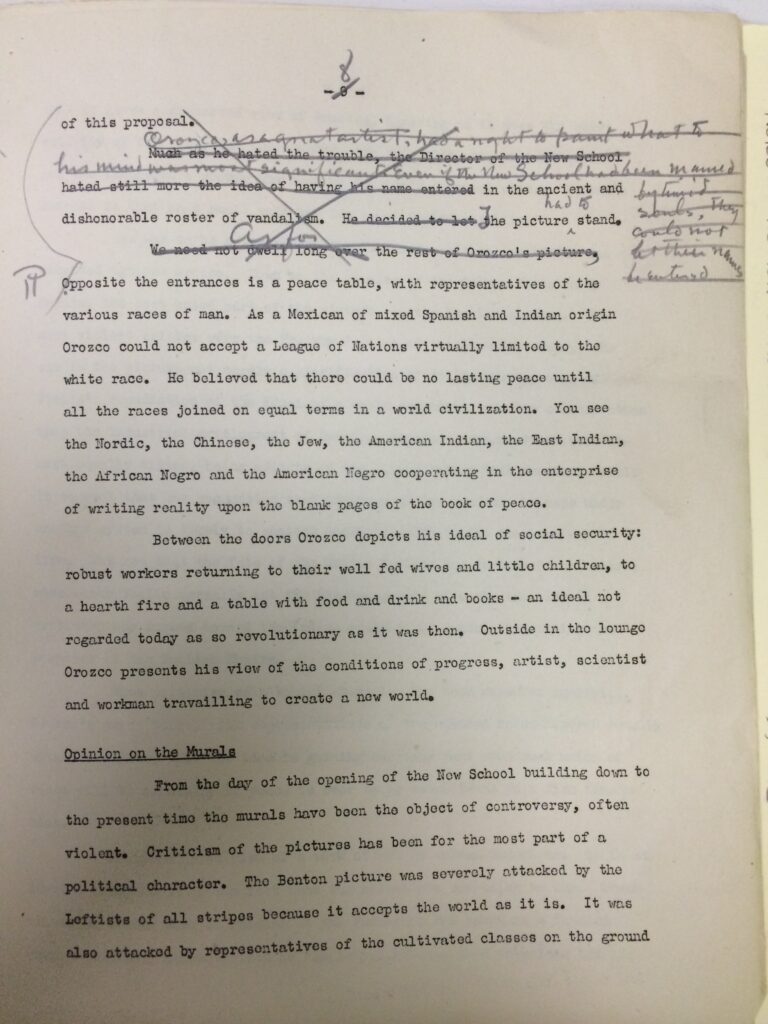

Alvin Johnson, the longstanding first Director of The New School, writes a brochure explaining the three original murals of the building by Thomas Hart Benton, José Clemente Orozco, and Camilo Egas, which includes mention of various criticisms that Orozco’s mural has provoked.

1947

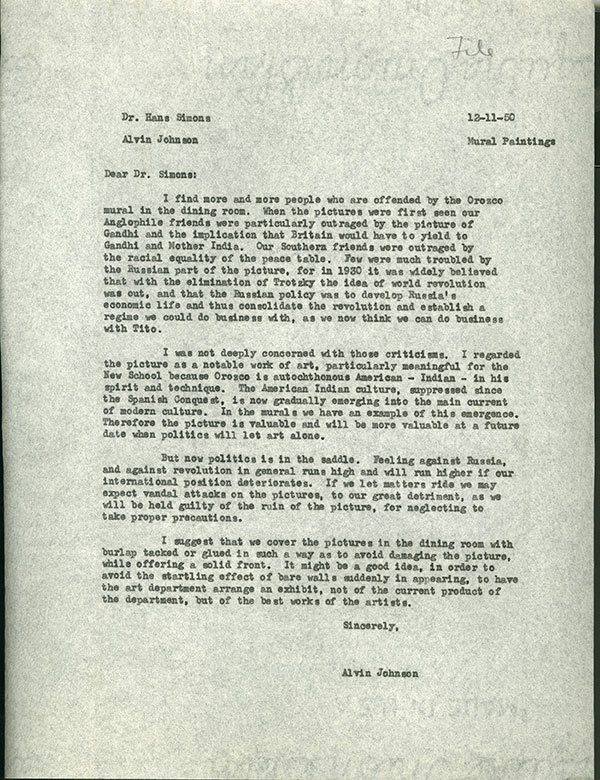

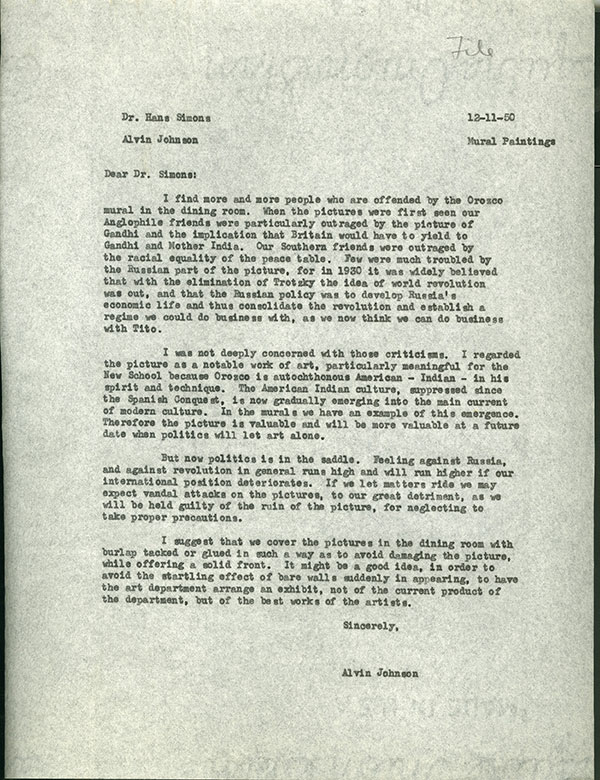

Alvin Johnson discusses with President Hans Simons the mounting criticism regarding the Orozco murals. He presents a stubborn defense of the murals to the outside while working to contain the controversy on the inside. Worried about vandalism to the fragile frescoes, Johnson recommends covering the pictures with “burlap tacked or glued in such a way as to avoid damaging the picture.” He also suggests arranging an art exhibit as a way in which to install such a covering so as not to gather undue attention.

1950

Alvin Johnson discusses with President Hans Simons the mounting criticism regarding the Orozco murals. He presents a stubborn defense of the murals to the outside while working to contain the controversy on the inside. Worried about vandalism to the fragile frescoes, Johnson recommends covering the pictures with “burlap tacked or glued in such a way as to avoid damaging the picture.” He also suggests arranging an art exhibit as a way in which to install such a covering so as not to gather undue attention.

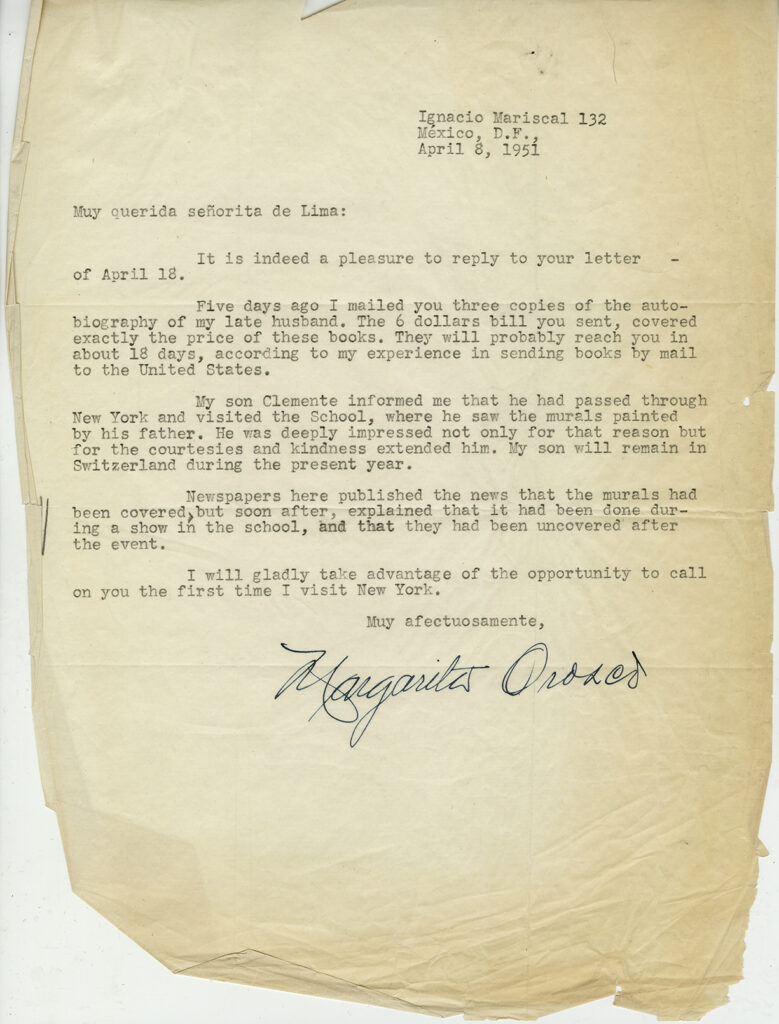

1951

The administration covers the murals for an exhibit of faculty artwork. After some protest by Artists Equity and others, the curtains are removed and a plaque put up that attributes the ideas in the mural exclusively to Orozco in 1930.

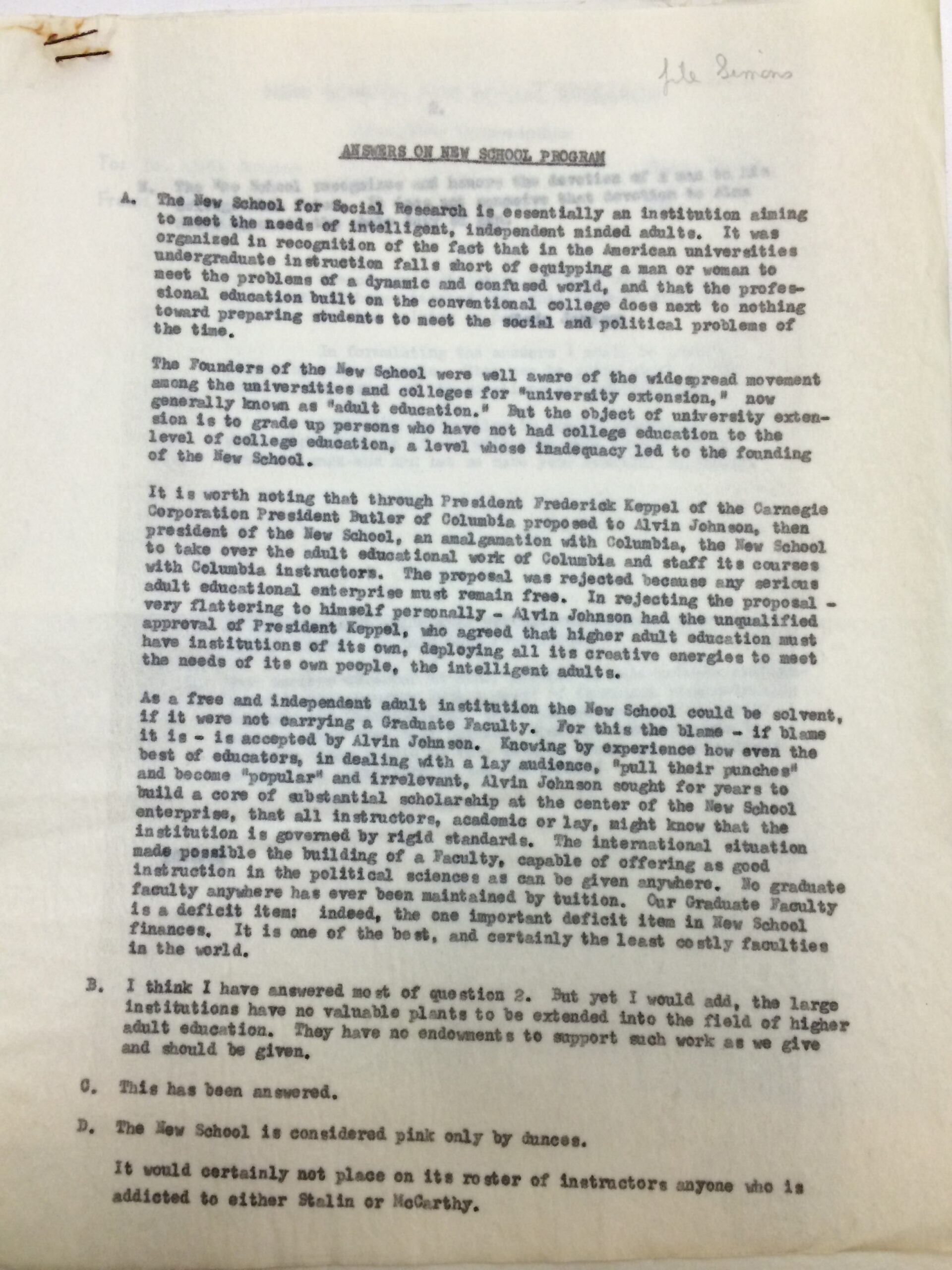

Queries increase regarding the school’s being “pink,” with “Communistic affiliations.” “The New School is considered pink only by dunces. It would certainly not place on its roster of instructors anyone who is addicted to either Stalin or McCarthy,” Johnson responds.

October 1951

1952

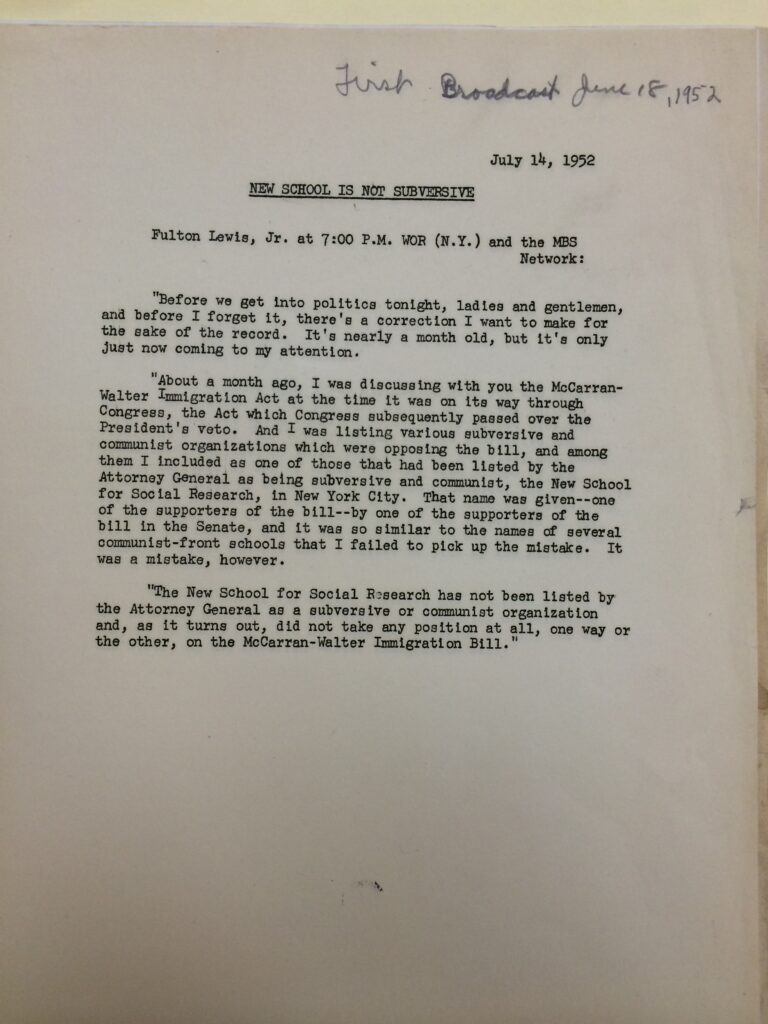

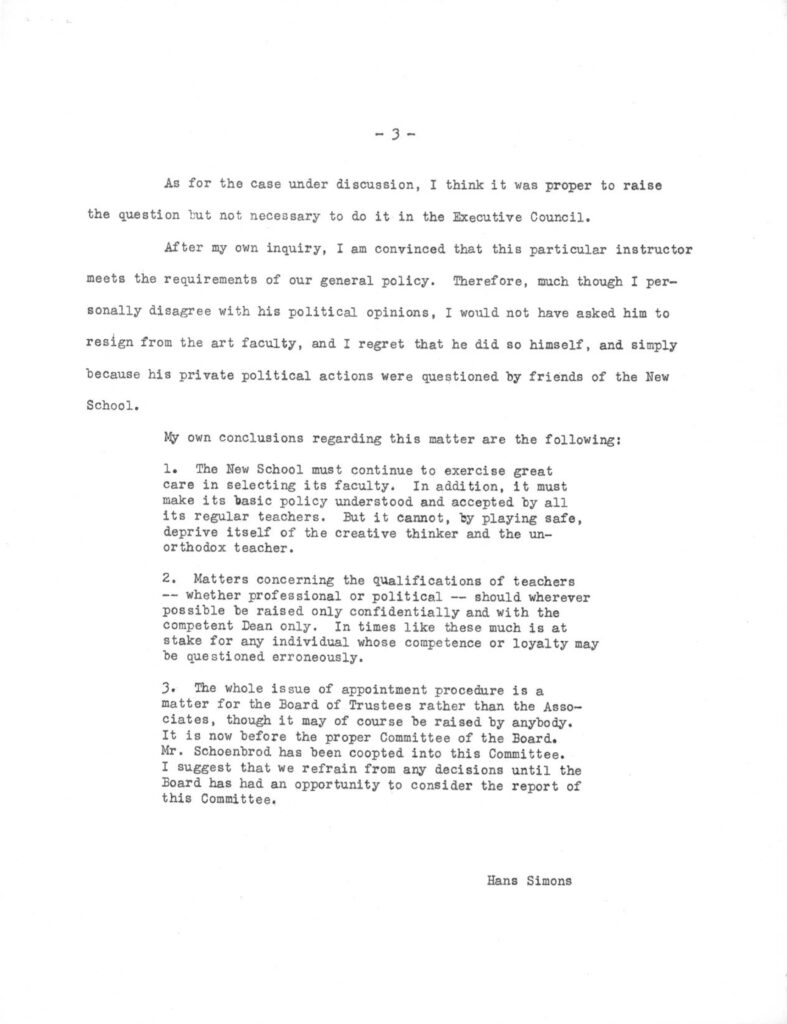

The New School continues to combat accusations of connections with Communism, denying the charges while also battling against the infringement of civil liberties. The head of the art department asks a faculty member to resign because of suspicions of Communist affiliations. President Simons urges caution in responding to such accusations. “In times like these much is at stake for any individual whose competence or loyalty may be questioned erroneously.”

1953

1952

The Board of Trustees forms a committee to investigate the question of “what should be done about the Orozco murals.” A report from Board of Trustee committee recognizes the artistic merit of the murals but also that their political content has “provoked controversy and stirred the prejudices of many people for many years” and has had an adverse effect on fundraising (in contrast to Johnson’s earlier public denial of any impact). The committee also asserts that the removal or destruction of the murals would betray the school’s “liberal tradition.” President Simons states his belief that “the most significant aspect of it was not the existence of the murals, but the fact that they were in the cafeteria so that students necessarily became a captive audience.” “[W]hichever way the school moves on this, about half the people will applaud and half will condemn,” he concludes.

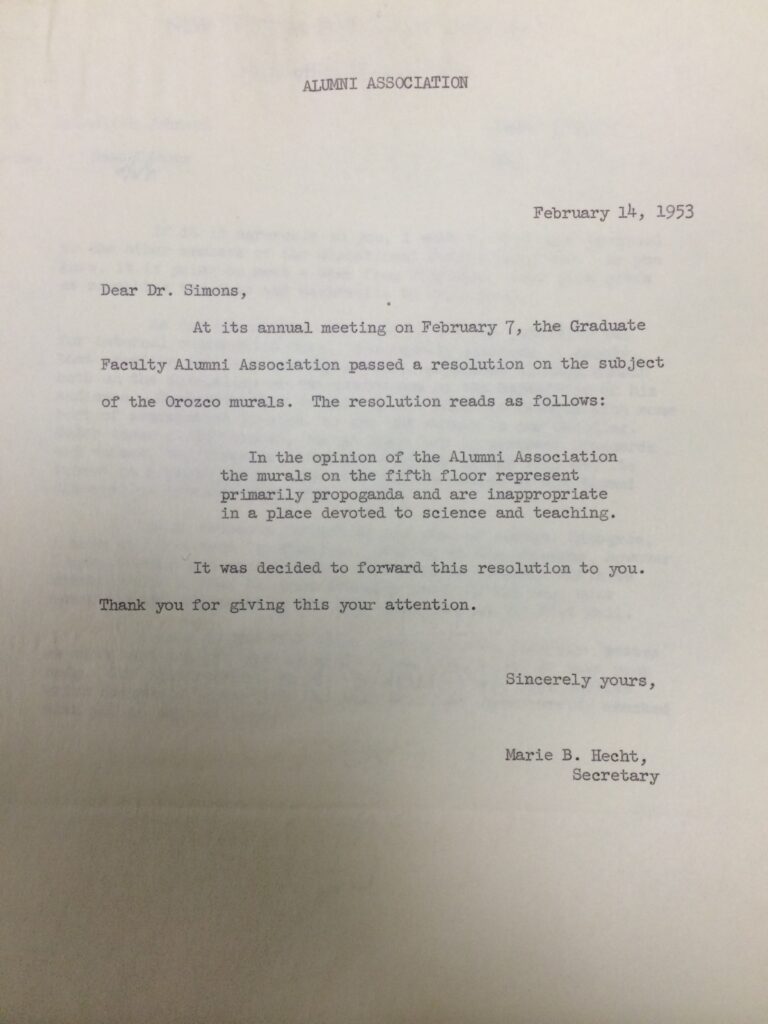

February 1953: The Graduate Faculty unanimously adopts a resolution declaring that the murals do not express the policy of the school. The resolution of its Alumni Association states that “the murals on the fifth floor represent primarily propaganda and are inappropriate in a place devoted to science and teaching.”

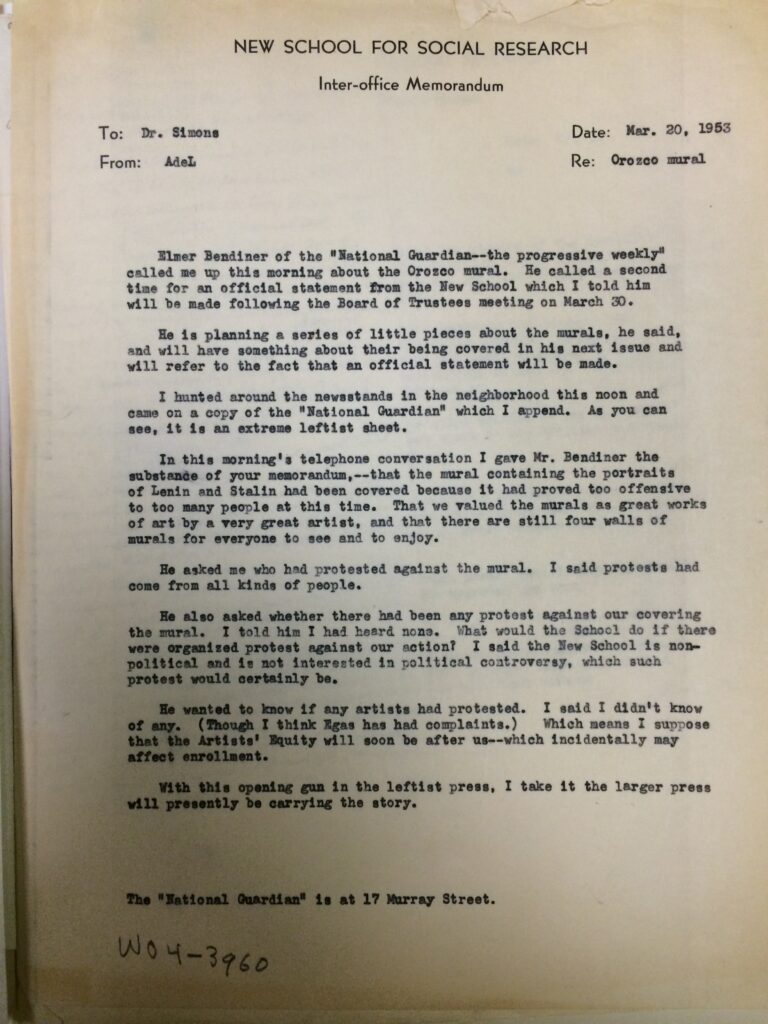

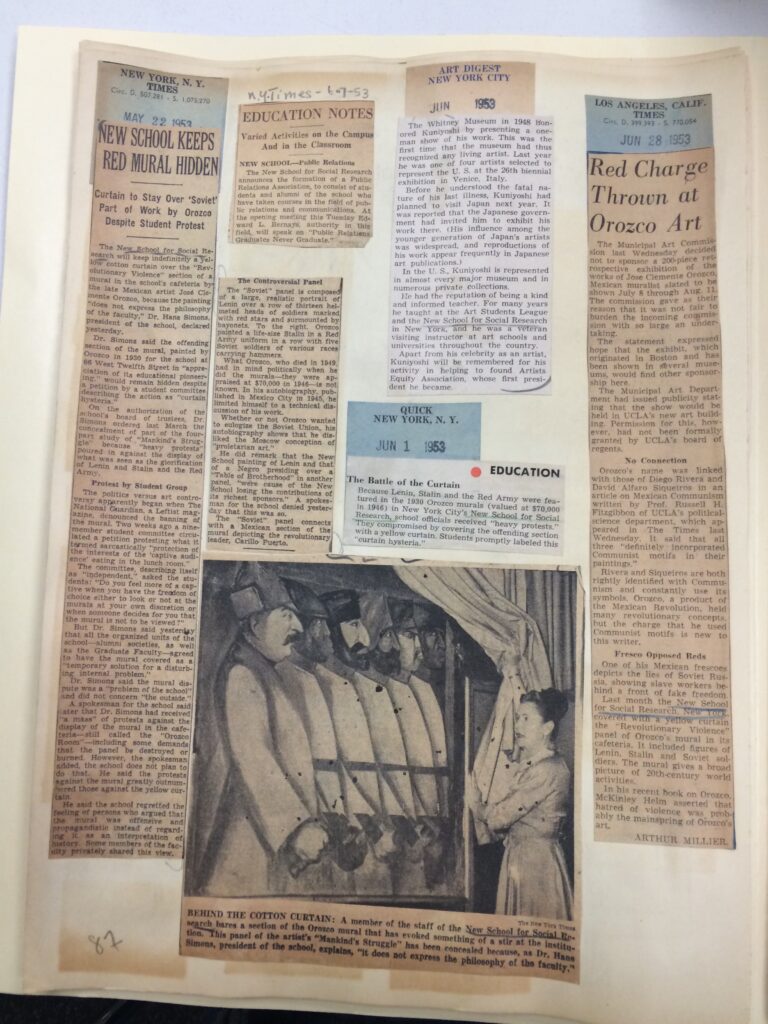

March-May 1953

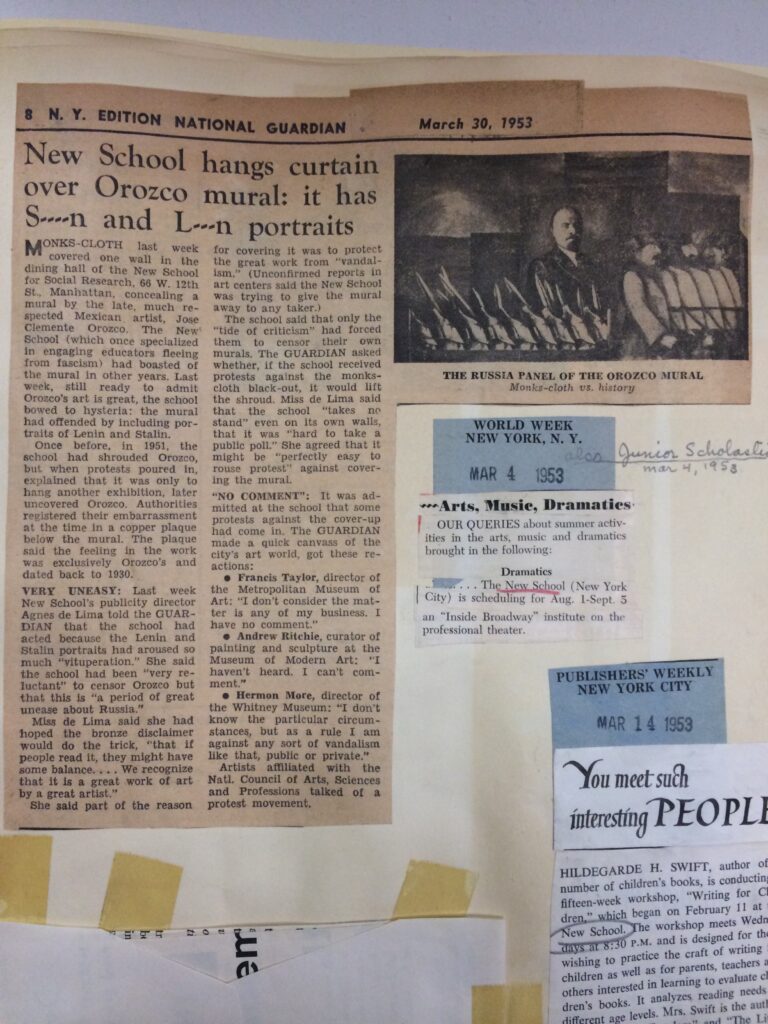

The Board of Trustee committee concludes that “the existence of the murals was clearly a divisive element and has caused considerable annoyance.” They authorize the President “to find some way of selling or otherwise disposing of the murals in a manner which would avoid their destruction and results in no cost to the school.” The committee also approves the President’s action in curtaining the wall that contains the most controversial subject matter.

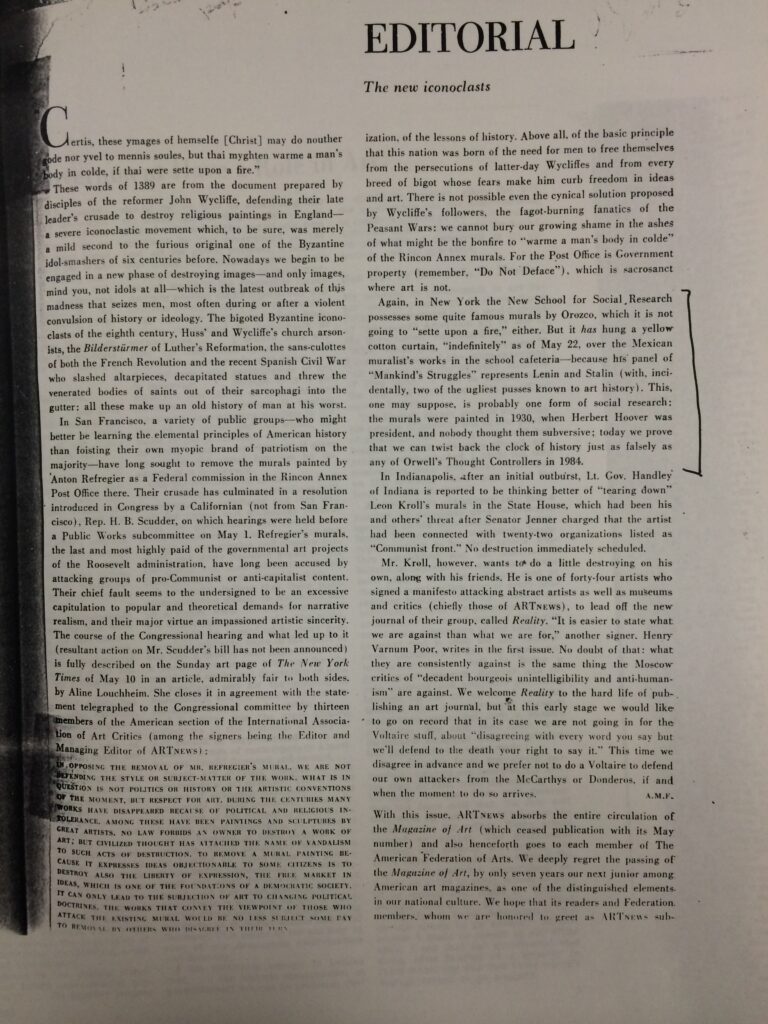

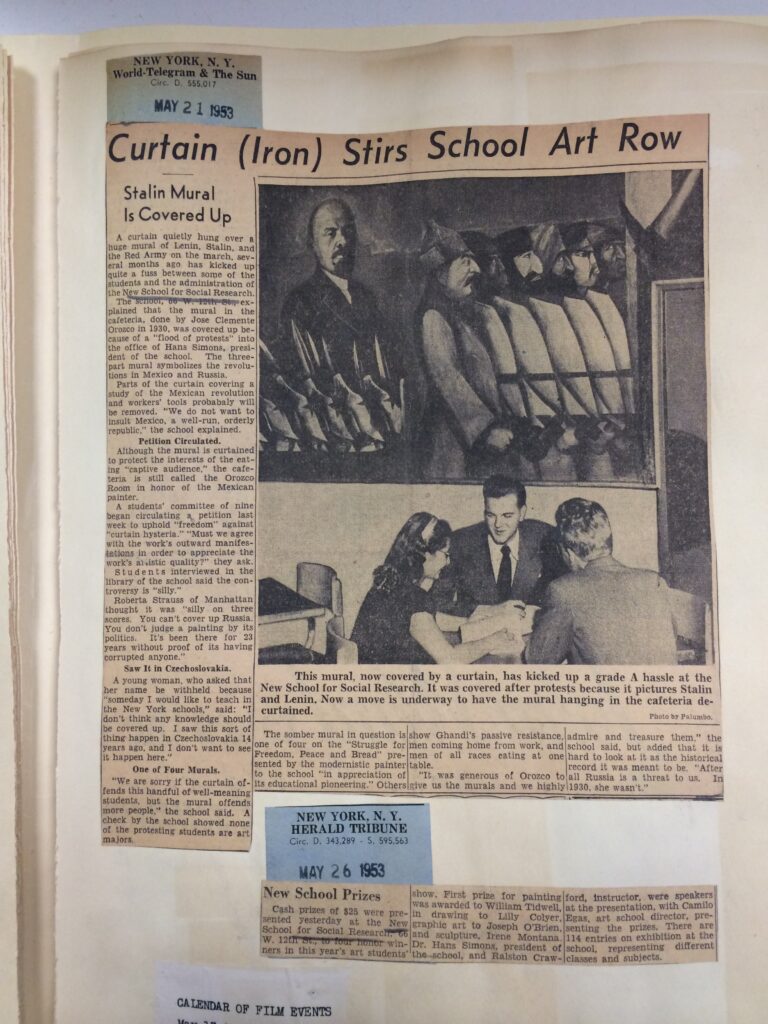

The covering of the murals provokes a variety of reactions in the press, most claiming that the school has “bowed to hysteria.”

May 1953

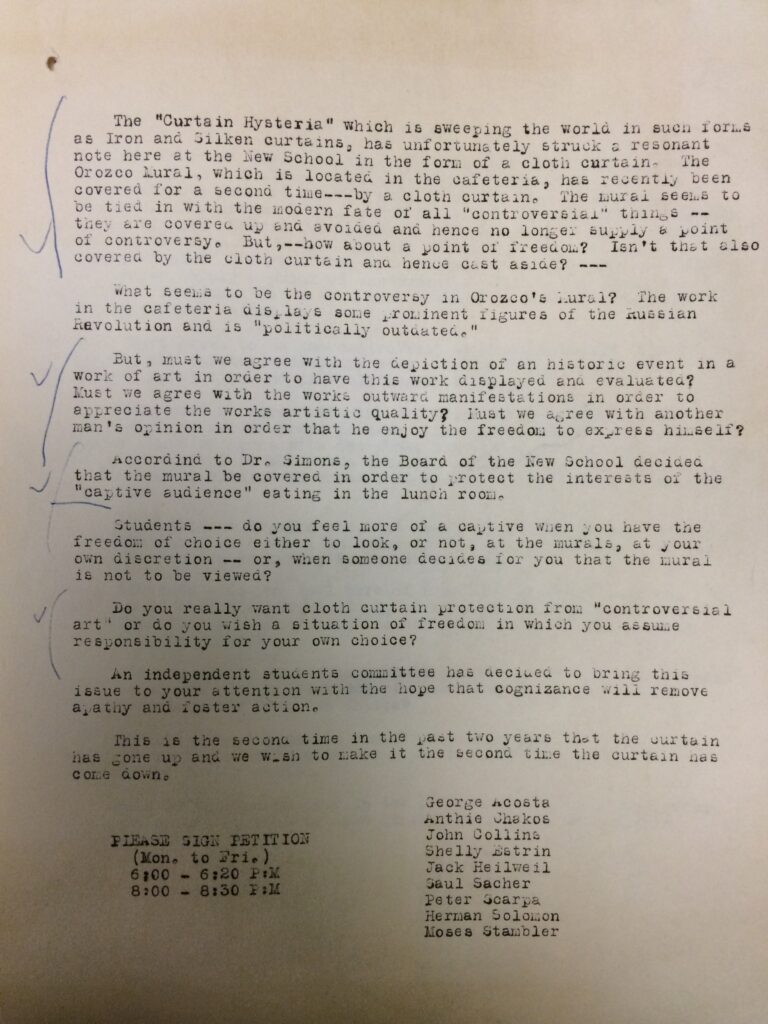

Students start a petition of protest. “The ‘Curtain Hysteria’ which is sweeping the world in such forms as Iron and Silken curtains, has unfortunately struck a resonant note here at the New School in the form of a cloth curtain,” students write. They berate the school for covering up controversy and debate, asking: “how about a point of freedom? Isn’t that also covered by the cloth curtain and hence cast aside?” “You can’t cover up Russia. You don’t judge a painting by its politics. It’s been there for 23 years without proof of its having corrupted anyone,” one student argues.

President Simons claims that the dispute is a “‘problem of the school’ and does not concern ‘the outside’.”

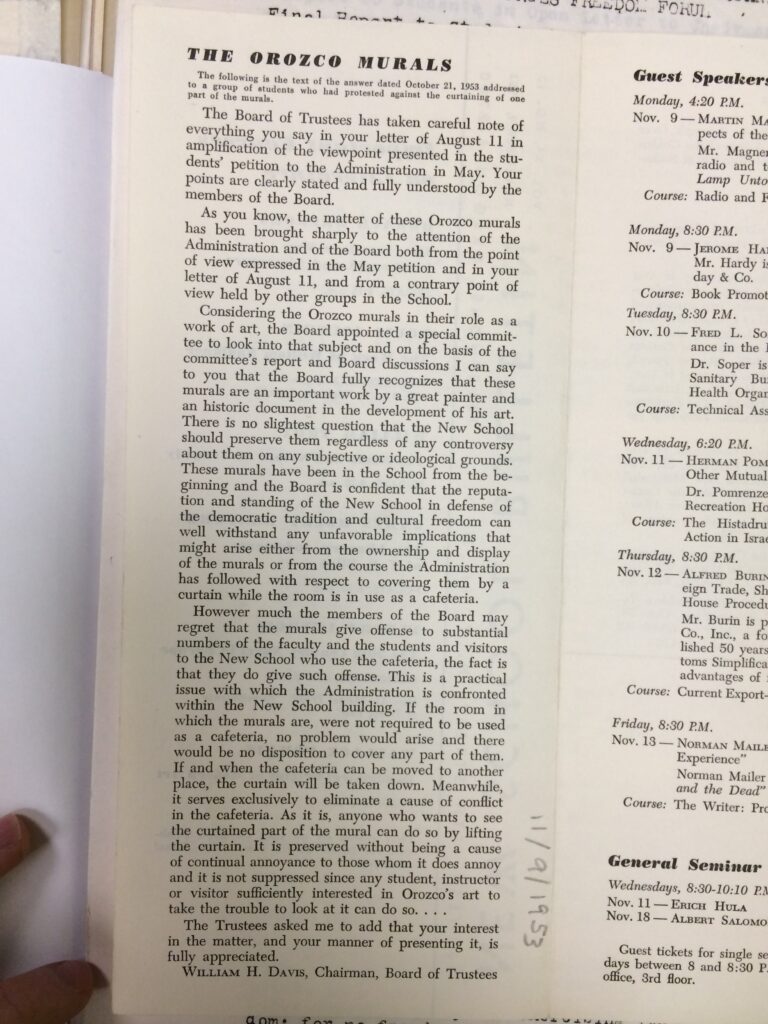

Oct 1953

Davis answers that the school is committed to preserving the murals. “The Board is confident that the reputation and standing of the New School in defense of the democratic tradition and cultural freedom can well withstand any unfavorable implications.”

Dec 1953: Students respond to the Board’s letter by announcing the dissolution of its Committee Against the Curtaining of Murals. But the students also make numerous recommendations intended to prompt continued widespread discussion about freedom, democracy, and the rights of minorities.

1954

Irving Howe, writing in the first issue of Dissent, condemns the New School for covering of the mural and President Simons’ understanding of the issue as an internal problem that did not concern “the outside.” Recalling the New School as a “refuge for liberalism and freedom,” Howe charges: “Well, Dr. Simons, one is sorry to say this, but the mural is not merely ‘a problem of the school’; and one would be delighted to go back where one came from: New York.”

The murals recede from the spotlight, as the room becomes a faculty lounge. Even events such as the luncheon celebrating the cornerstone of a new building (65 W. 11th St.) are located in the space outside the Orozco Room rather than within it.

1962: At a meeting held in the Orozco Room, Board of Trustee members Ralph Walker and Alvin Johnson congratulate President Henry David for taking off the covering of the mural and bringing the room back into use.