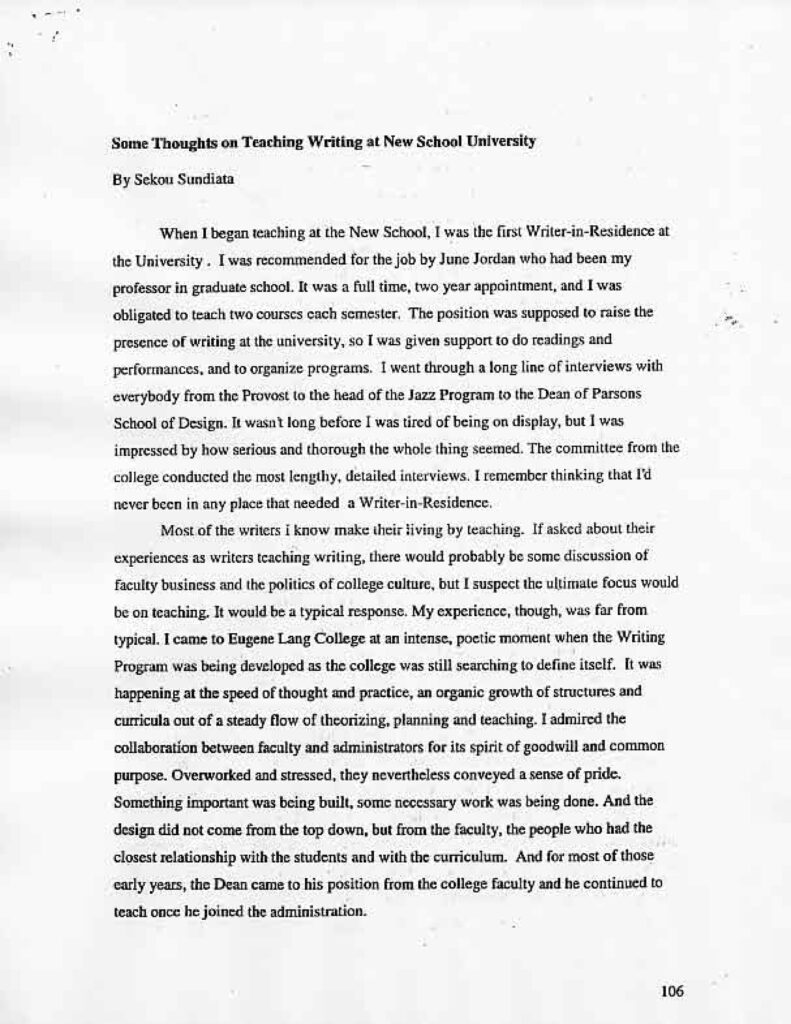

The Matsunaga Affair Chronology

September 1989

In response to political attacks on artistic freedom, the University explicitly extends its 1987 Policy on Free Exchange of Ideas to art and design. Going beyond pledges of academic and artistic freedom, these statements articulate the responsibilities of the university and its faculty in maintaining an environment open to these freedoms.

At Convocation New School President Jonathan Fanton describes the forthcoming Statement on Freedom of Artistic Expression and also makes a commitment to make the university a more welcoming place for all people: The New School stands behind its members’ “right to be free from intolerance.”

October 1989

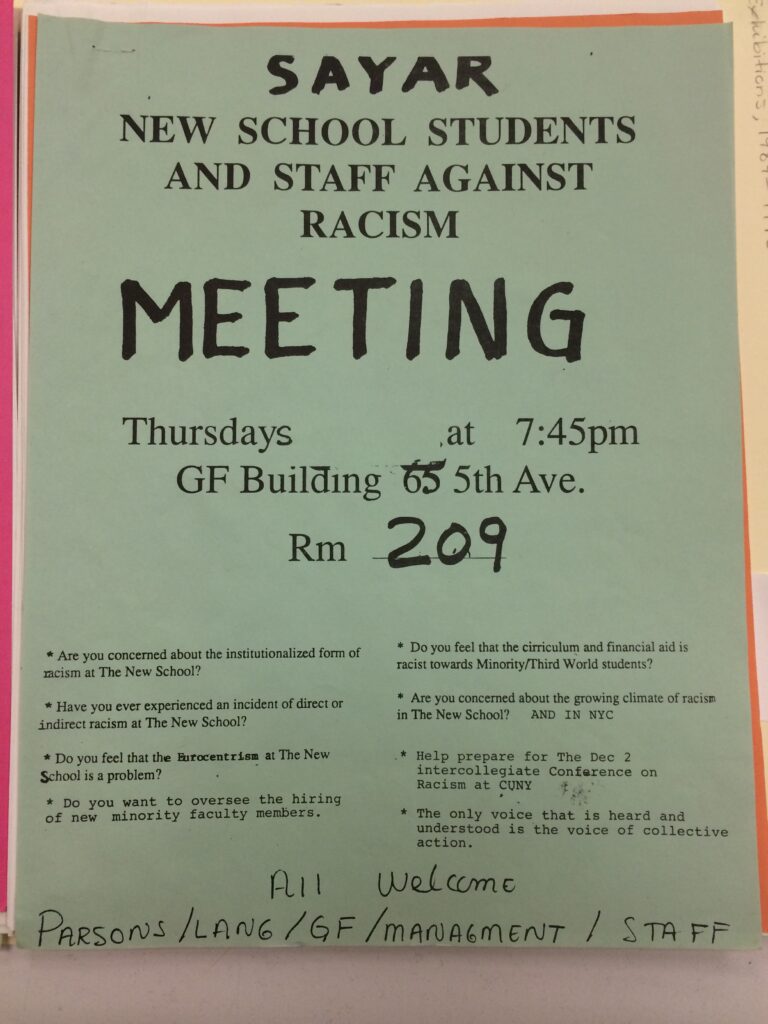

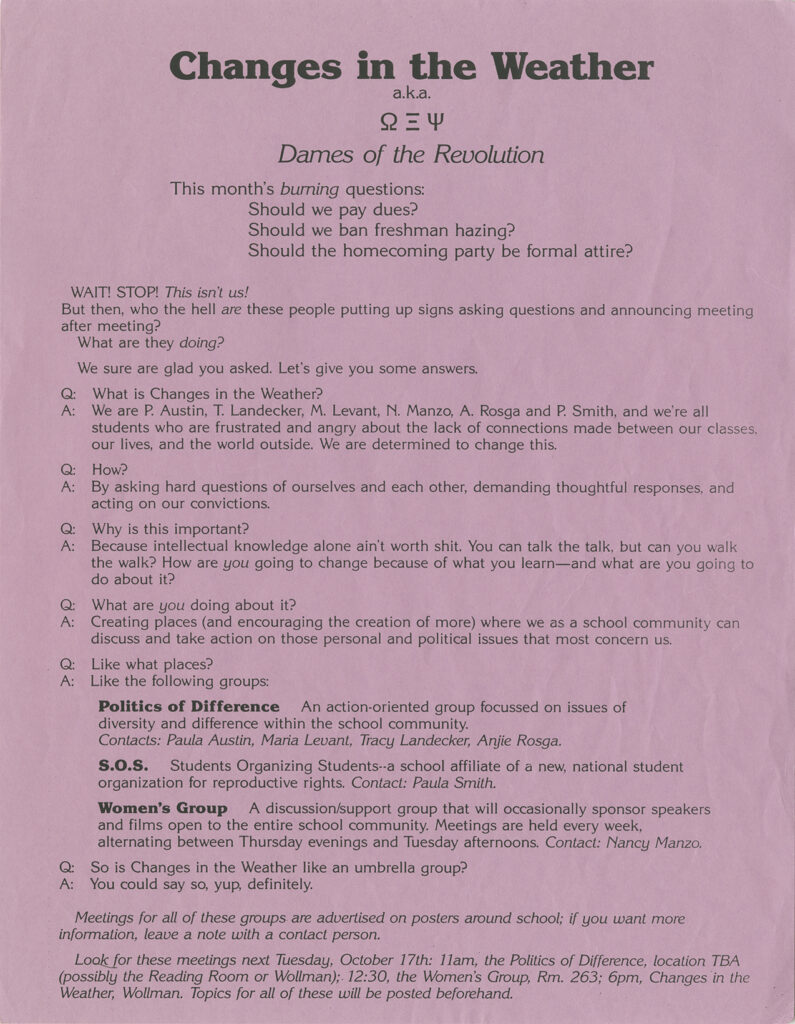

It is a time of political organizing among students at The New School. Weekly meetings are held by Students and Youth against Racism (SAYAR). Changes in the Weather is created as an “umbrella group” for discussions to address the “lack of connections made between our classes, our lives, and the world outside,” especially on questions of gender, sexuality and race, at Eugene Lang College.

October 18

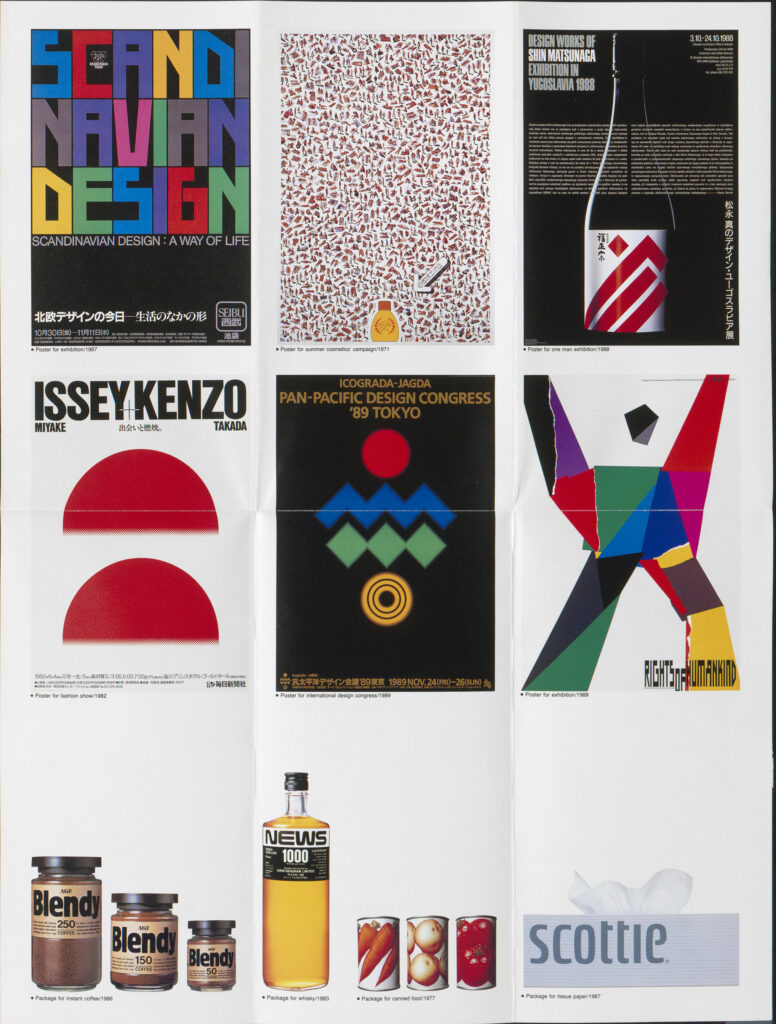

An exhibition of works by Japanese graphic designer Shin Matsunaga opens at the Parsons Galleries. Parsons’ Chancellor David Levy commends the “inventive and far-reaching” work; “blending a Japanese calligraphic sensibility with modern typography and western approaches to graphic design” it “provides a deep and educational experience into the working of the graphic process.” Matsunaga’s first show in the U.S., it comprises 350 works spread over three gallery spaces. The space visible from Fifth Avenue includes small posters that Matsunaga’s company used for in-house celebrations of successful and beloved projects.

October 24

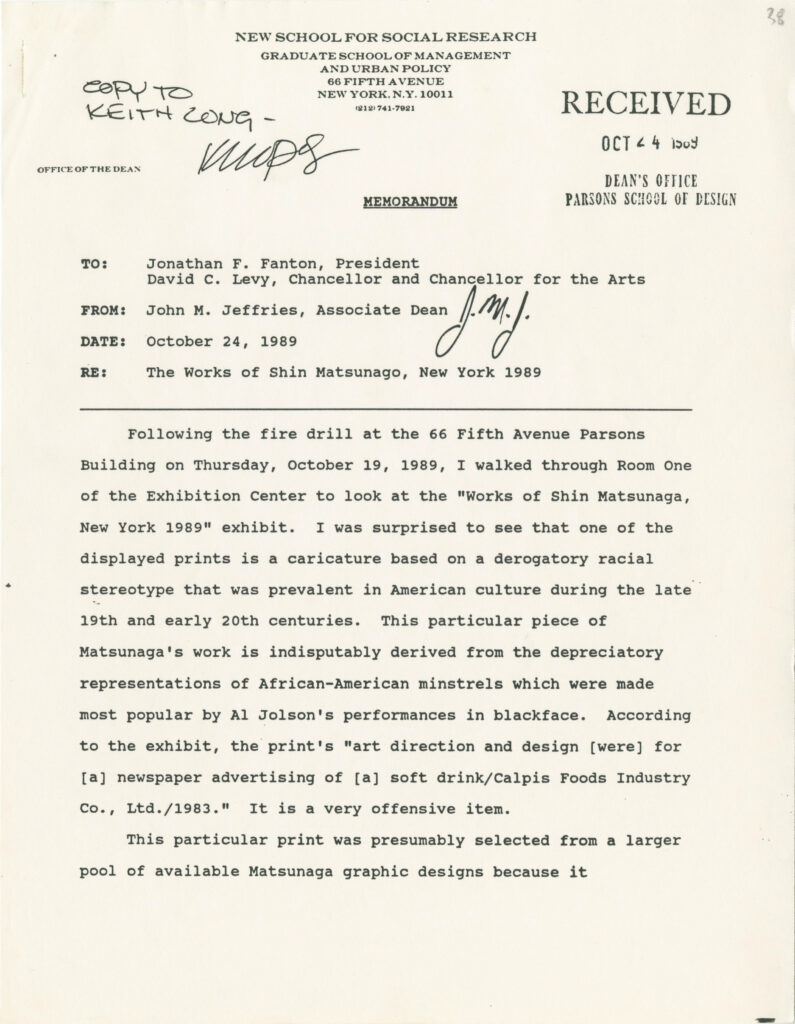

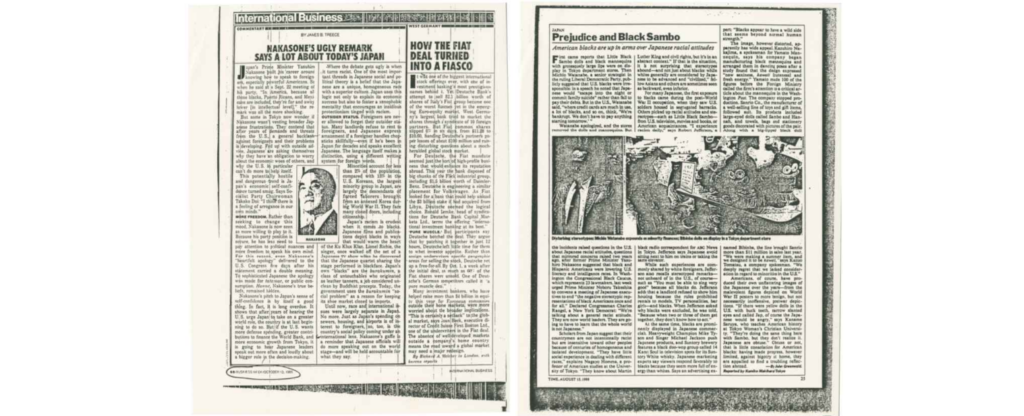

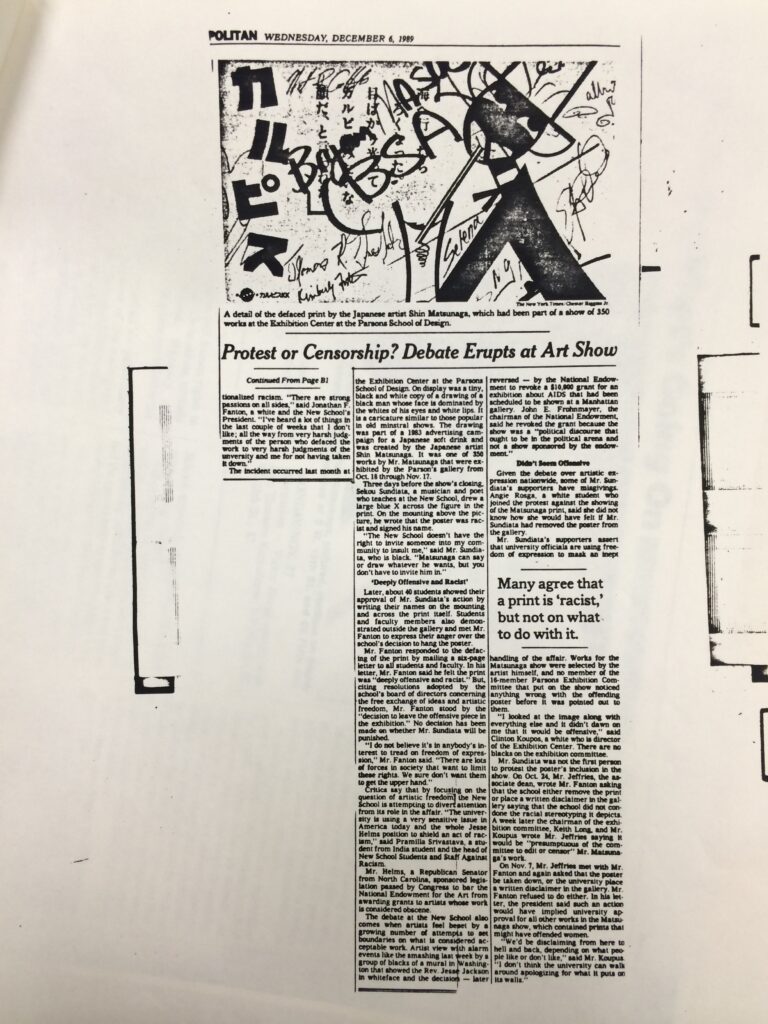

One of the small posters in the small gallery is a 1987 newspaper advertisement for Calpis, which includes its racist logo. Associate Dean of Milano School of Management John M. Jeffries sees it and writes a letter to Fanton and Levy. He describes the image and the “pain” of encountering it – “especially at The New School and just weeks after the president’s commitment to creating a more inclusive university environment.” Jeffries appends copies of recent articles from American magazines about racist imagery in Japanese popular culture.

October 31

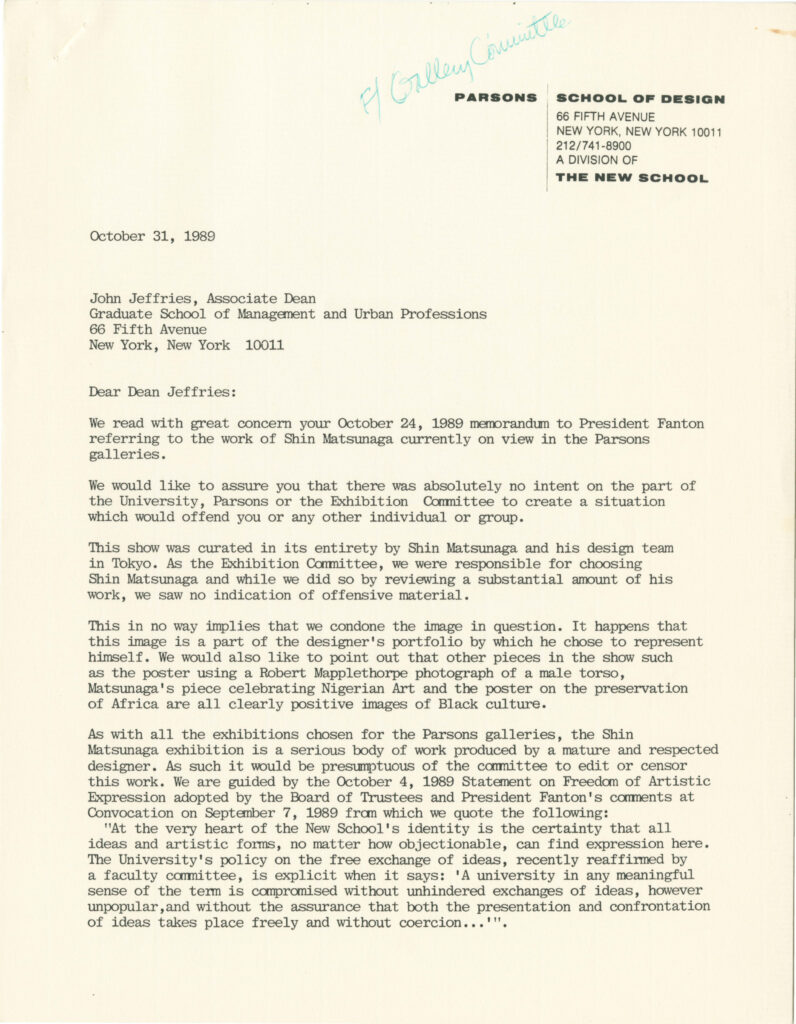

Chairman of the Parsons Exhibition Committee Keith Long responds to Jeffries. Procedures were followed and there was “no intention to offend.” The exhibition was curated “in its entirety” by Matsunaga and his team in Tokyo. Especially in light of the Statement on Freedom of Artistic Expression, it “would be presumptuous of the committee to edit or censor this work.” The exhibition remains unchanged.

November 7

On the day New Yorkers elect their first African American mayor, David Dinkins, Jeffries meets with Fanton and asks that the Calpis image be taken down or that a written disclaimer be put up next to it. Fanton refuses on the grounds that “such an action would have implied university approval for all other works in the Matsunaga show, which contained prints that might have offended women.”

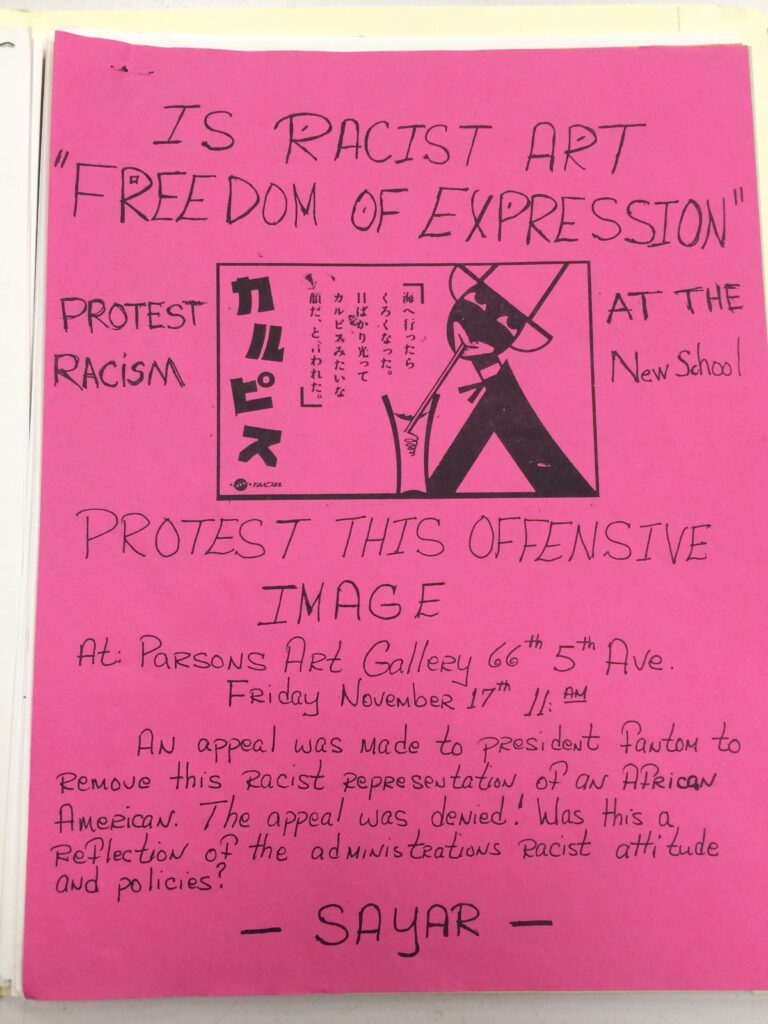

Amid a variety of discussions pink flyers sporting the Calpis image appear. SAYAR (Students and Youth against Racism) announces a protest for November 17, the day the exhibition closes, asking: “Is racist art ‘freedom of expression’?”

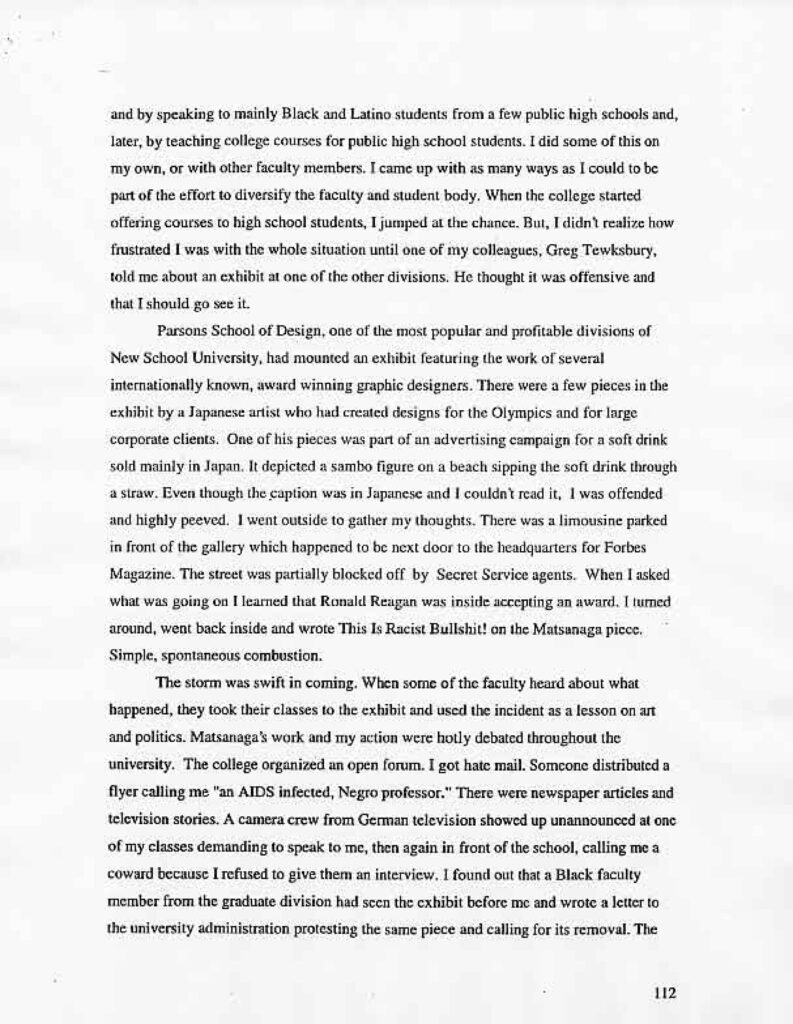

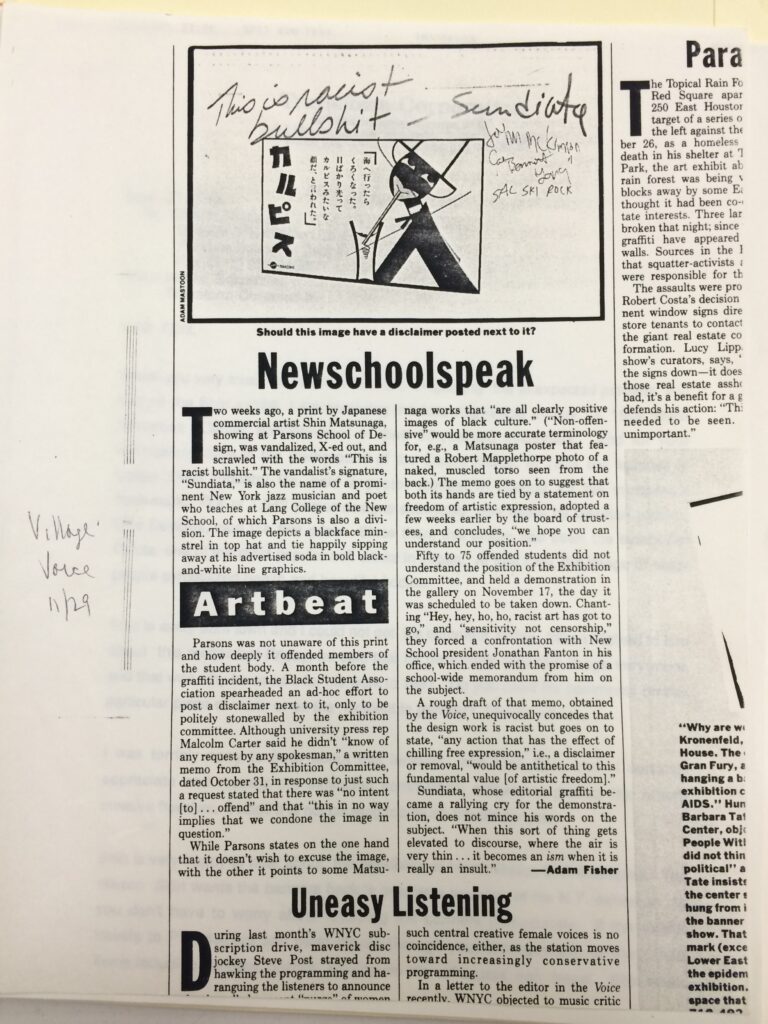

November 14

Sekou Sundiata, urged to visit the exhibit by Lang colleague Gregory Tewksbury, seeks out the Calpis image. In an unpublished essay on teaching writing at The New School, written some years later, Sundiata describes what happened. “Offended and highly peeved,” he leaves the building only to encounter the limousine of ex-president Ronald Reagan, who was receiving a prize in the Forbes building next door. Sundiata returns to the gallery and in an act of “simple, spontanous combustion” crosses the image out. “This is racist bullshit,” he writes above it and signs his name. Soon, dozens of students add their names in support.

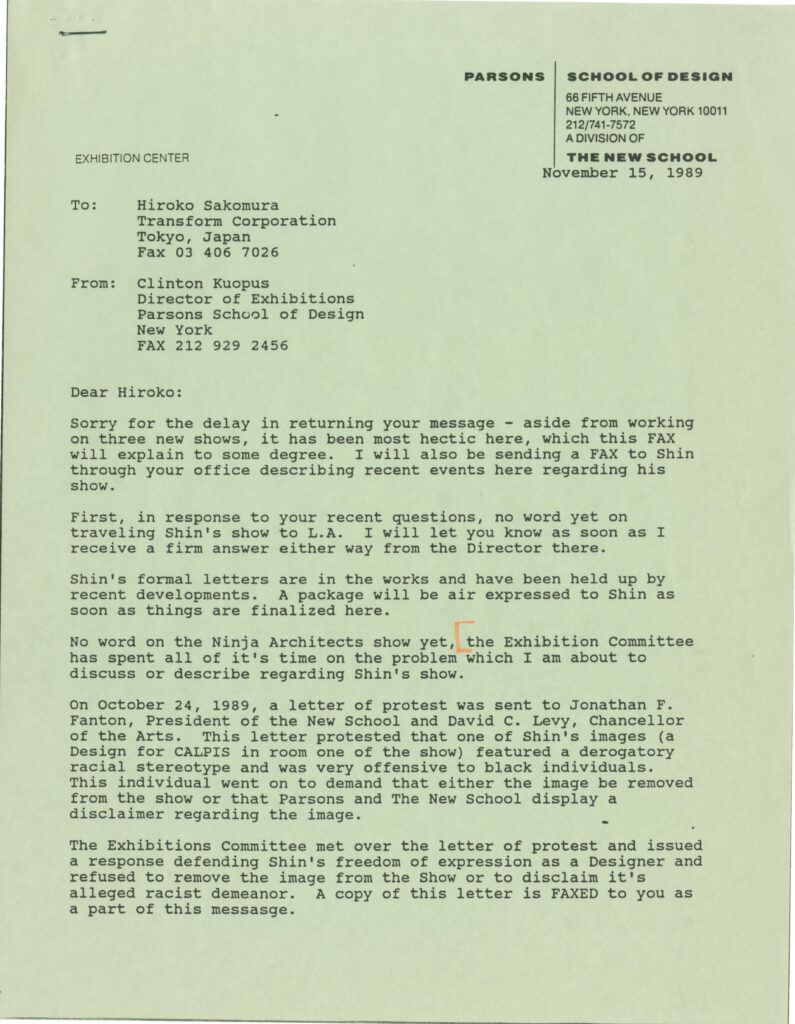

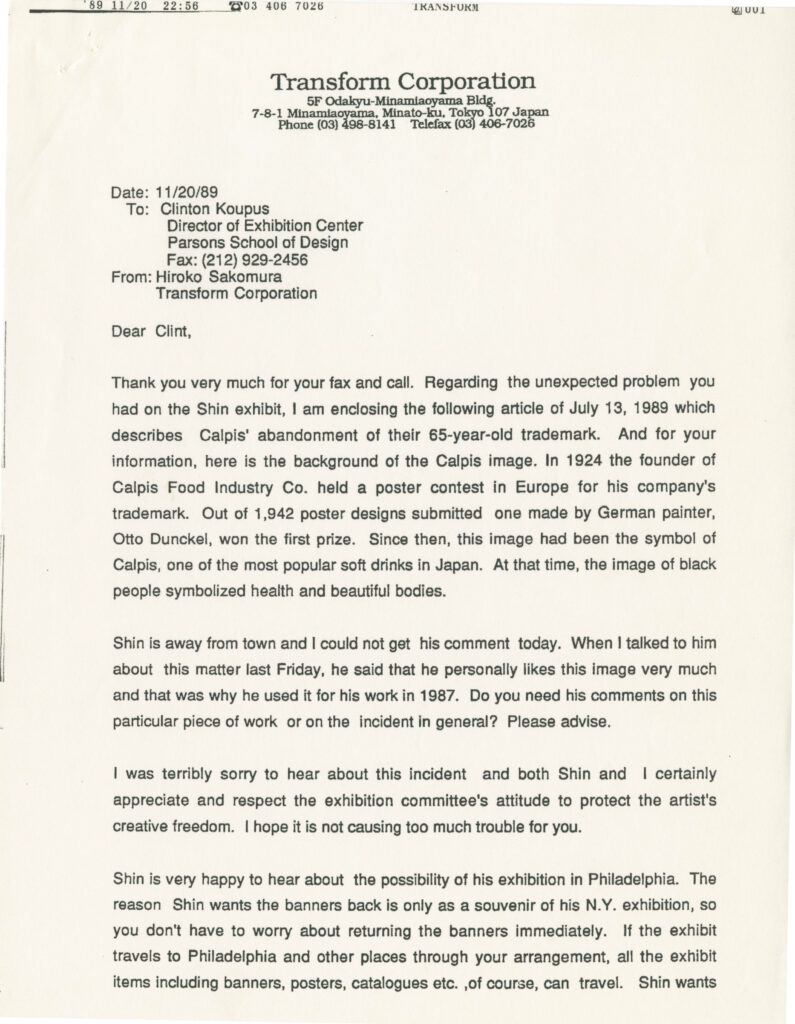

November 15

Director of Exhibitions Clinton Kuopus writes to Hiroko Sakomura, liaison to Matsunaga, to describe what has happened. Sakomura responds quickly, explaining the history of the Calpis logo. It was designed by German painter Otto Dunckel in 1924 at a time when “the image of black people symbolized health and beautiful bodies” in Japan. An appended article from the Japan Times confirms that the logo was officially retired in July.

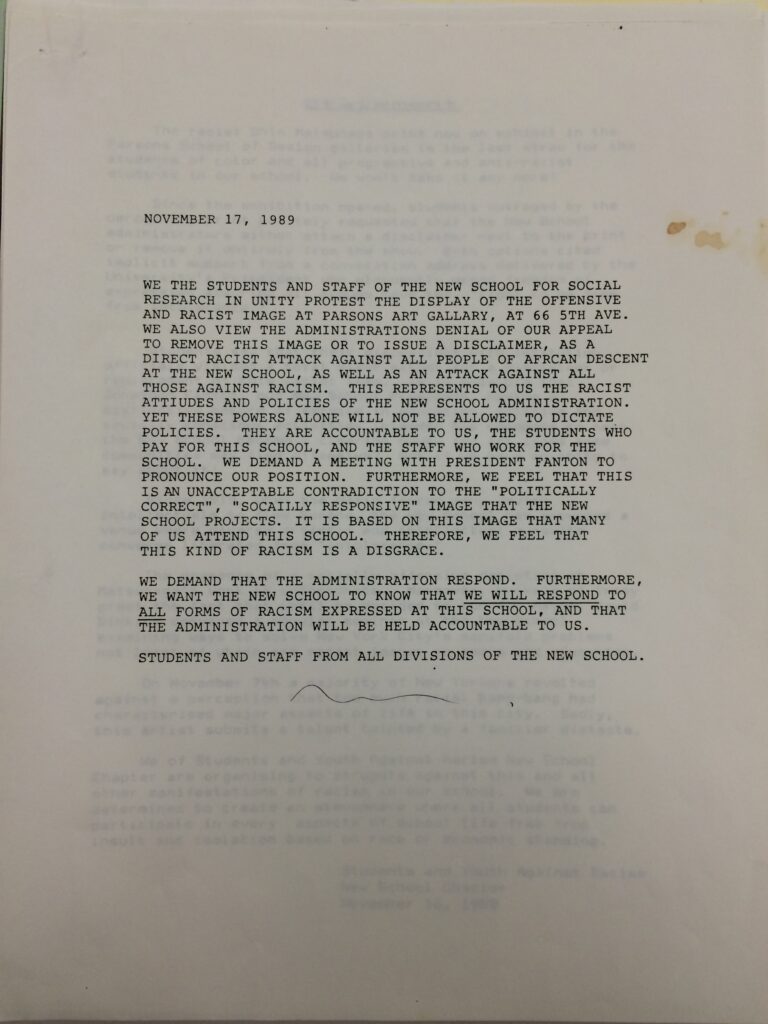

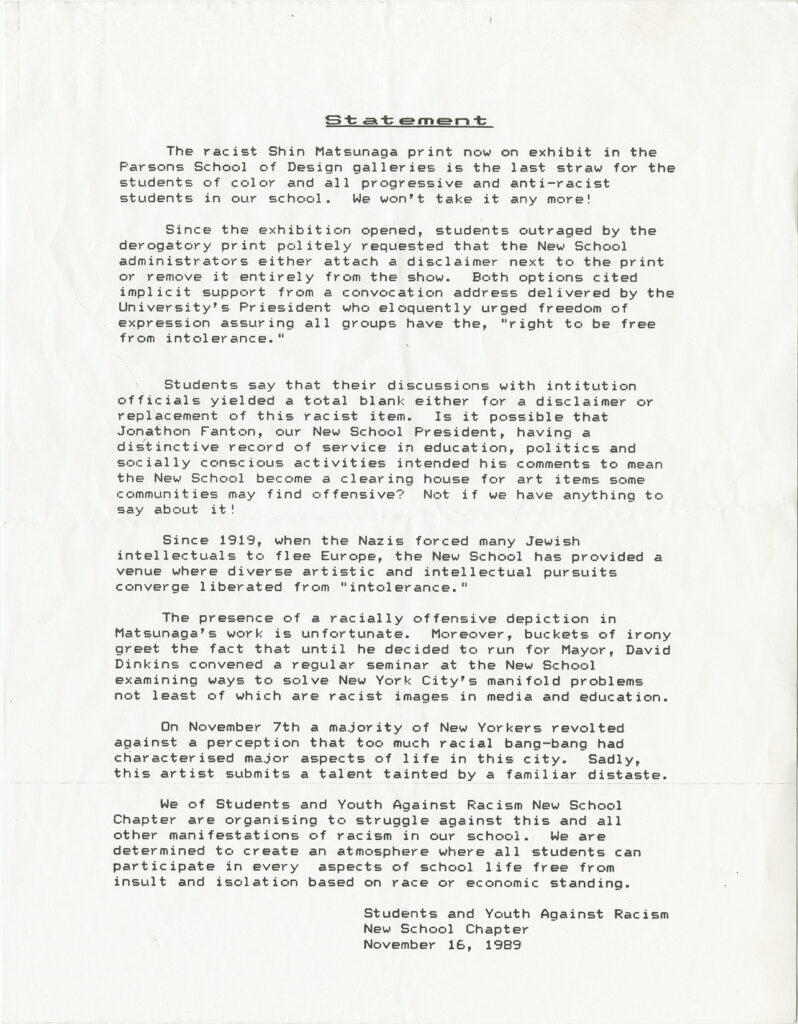

November 17

The exhibition closes in a flurry of protest. A statement from “New School Students and Staff” deplores the image and the administration’s refusal to take the offending image down or accompany it with a disclaimer: “this kind of racism is a disgrace.” 50-75 people march to the President’s Office. Under pressure Fanton promises to pen a school-wide statement on the topic.

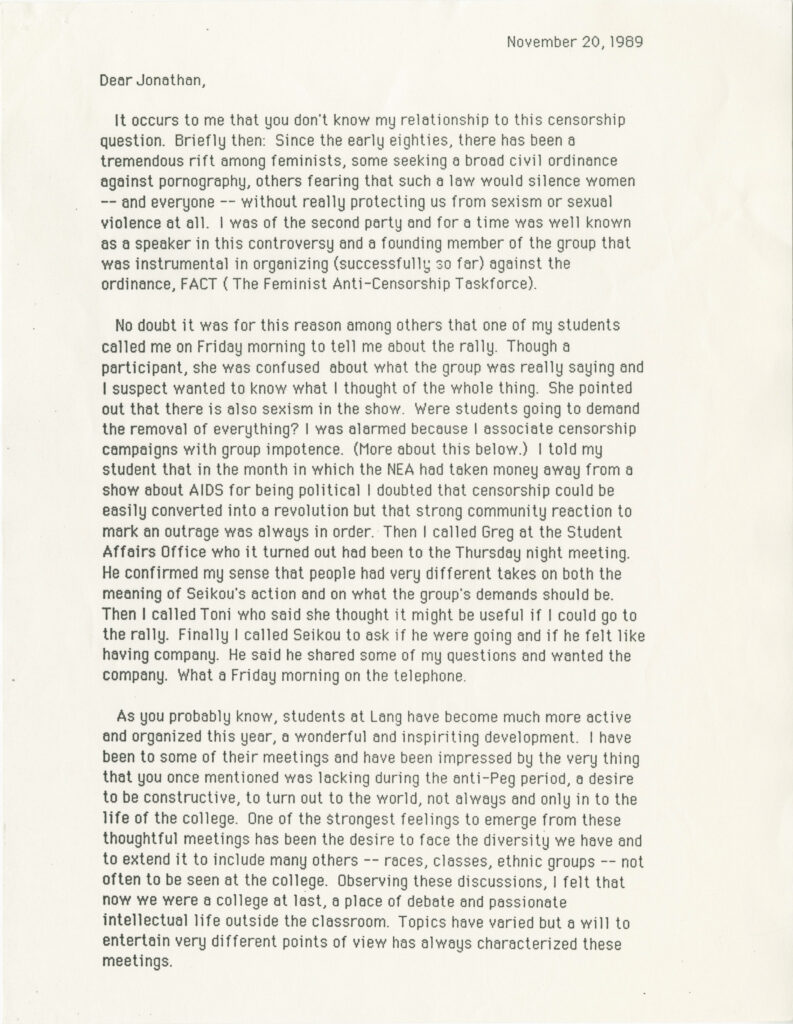

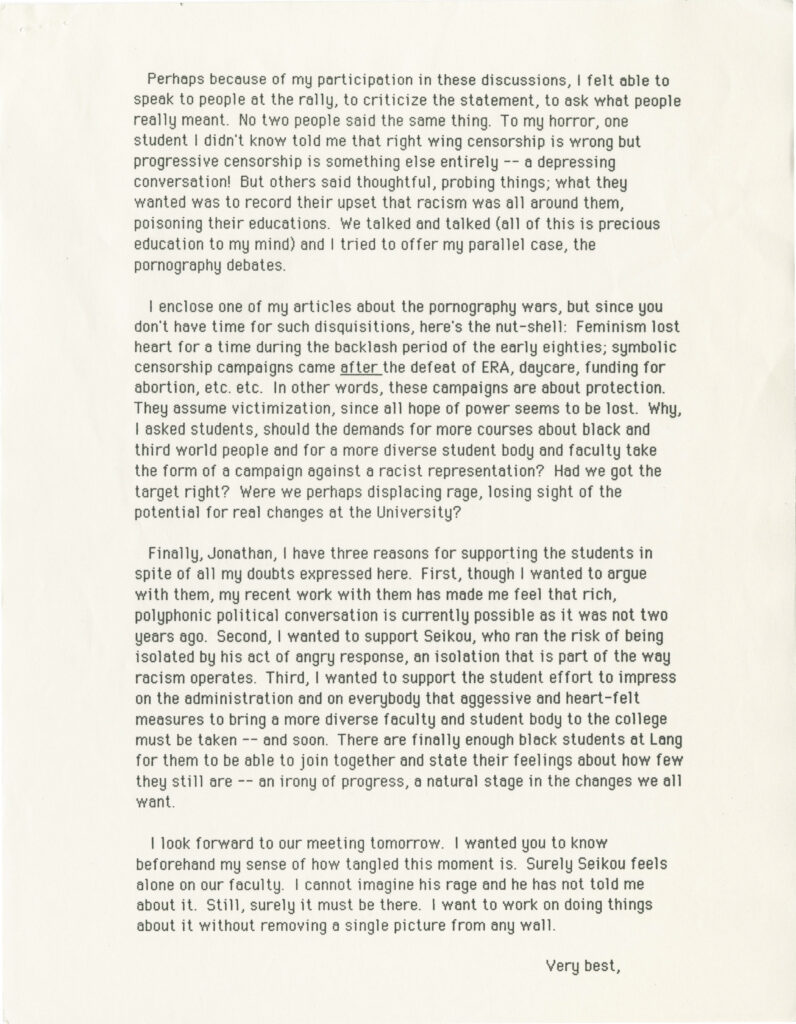

November 20

Lang faculty member Ann Snitow writes a letter to Fanton, describing the increasingly robust political culture of Lang and explaining her participation in the siege of his office. While she “associate[s] censorship campaigns with group impotence,” she supports the students in their protest. “There are finally enough black students at Lang for them to be able to join together and state their feelings about how few they still are – an irony of progress.” Snitow joins other Lang faculty members in a meeting with Fanton.

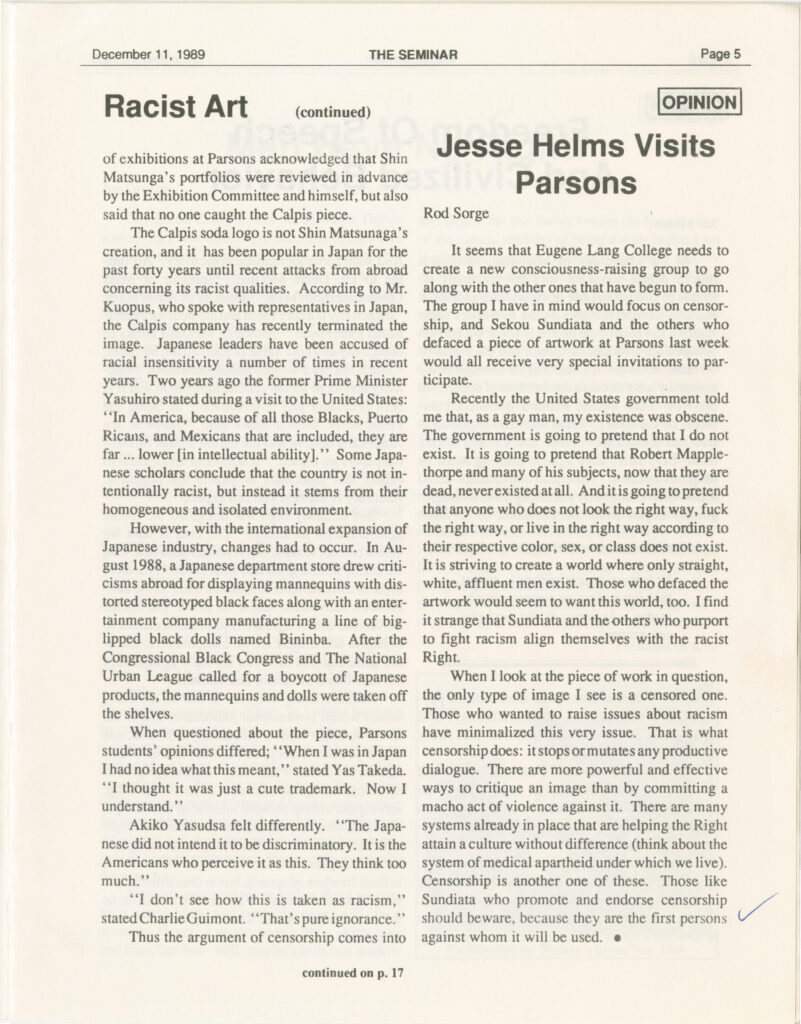

November 21

In a letter to the university community, Fanton characterizes the controversy as an instance “when the values of freedom of expression and freedom from intolerance and harassment come into conflict.” He too finds the Calpis image “deeply offensive and racist,” expressing gratitude for the protest against it, but invokes the Statement on Artistic Freedom: “the university does not and cannot sponsor, or give approval or disapproval to, the content of speech, written expression, or works of art, design, and performance.” It has no “official” sanction to give or withdraw. At a time when Jesse Helms is pushing legislation to censor the National Endowment for the Arts, the university should stand together for freedom of expression precisely as the best vehicle to bringing about an end to intolerance.

November 29

The controversy gains the attention of the Village Voice and, a week later, the New York Times. Sundiata defends his action to the media: “The New School doesn’t have the right to invite someone into my community to insult me. Matsunaga can say or draw whatever he wants, but you don’t have to invite him in.”

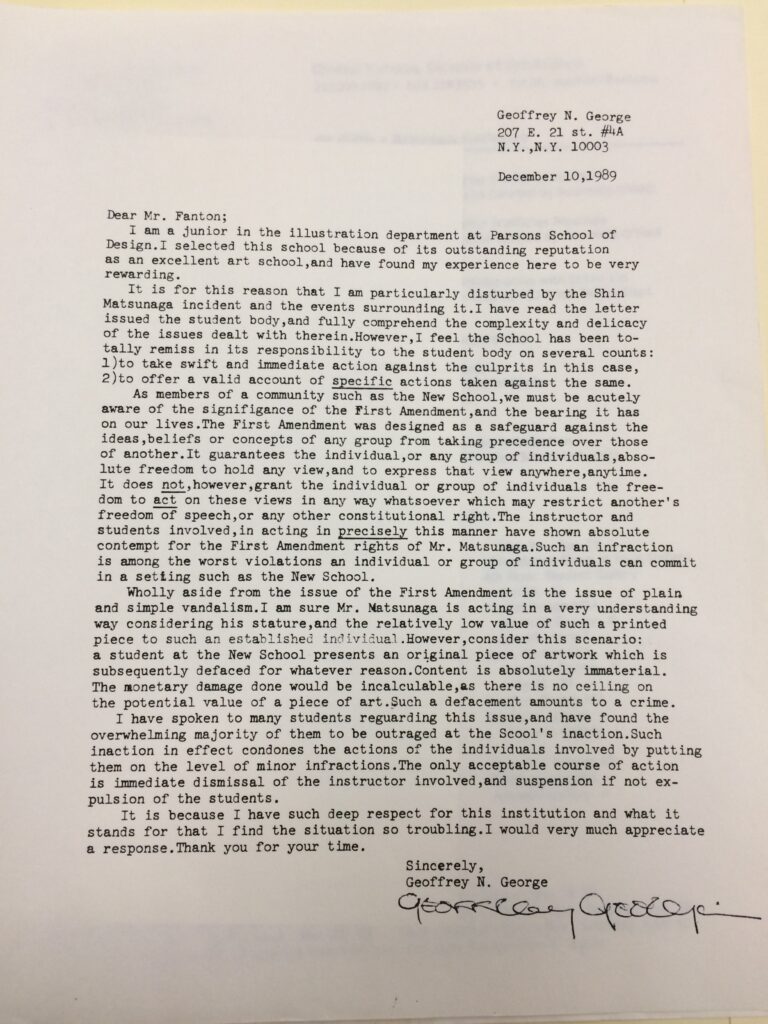

December 10

Claiming to write for the “overwhelming majority” of his fellow students, an undergraduate at Parsons upset at Sundiata’s “vandalism” and the university’s reaction to it writes to Fanton. The student demands that Sundiata be fired and that those who signed their names in support be suspended or expelled.

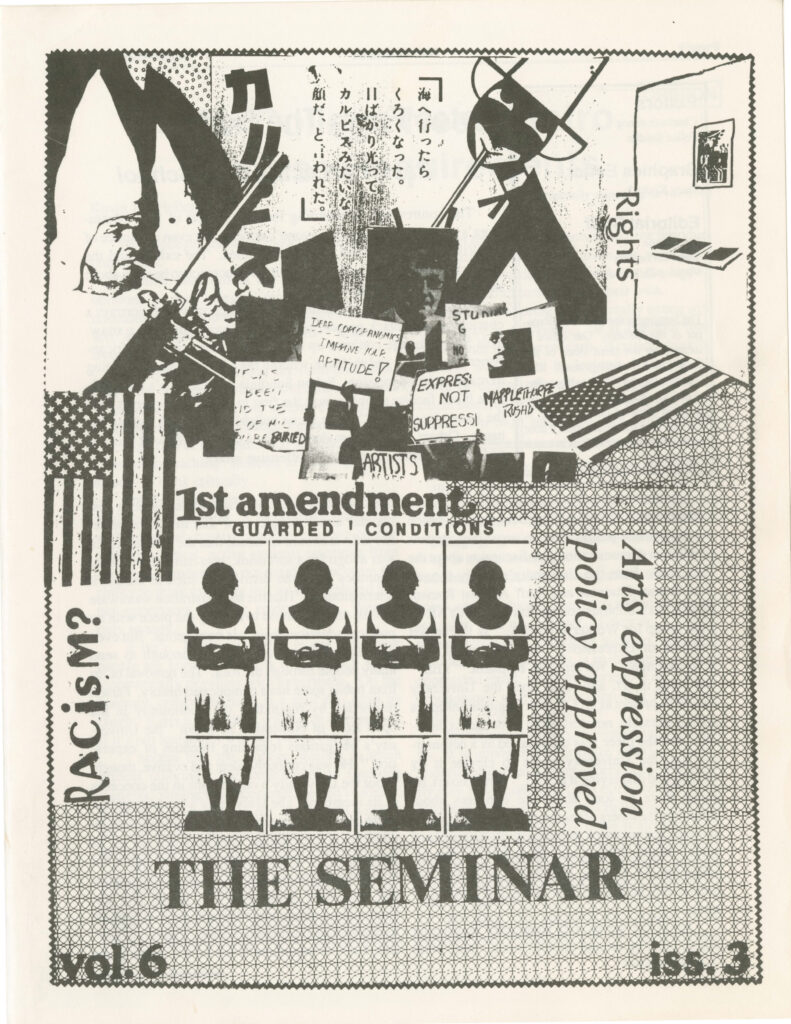

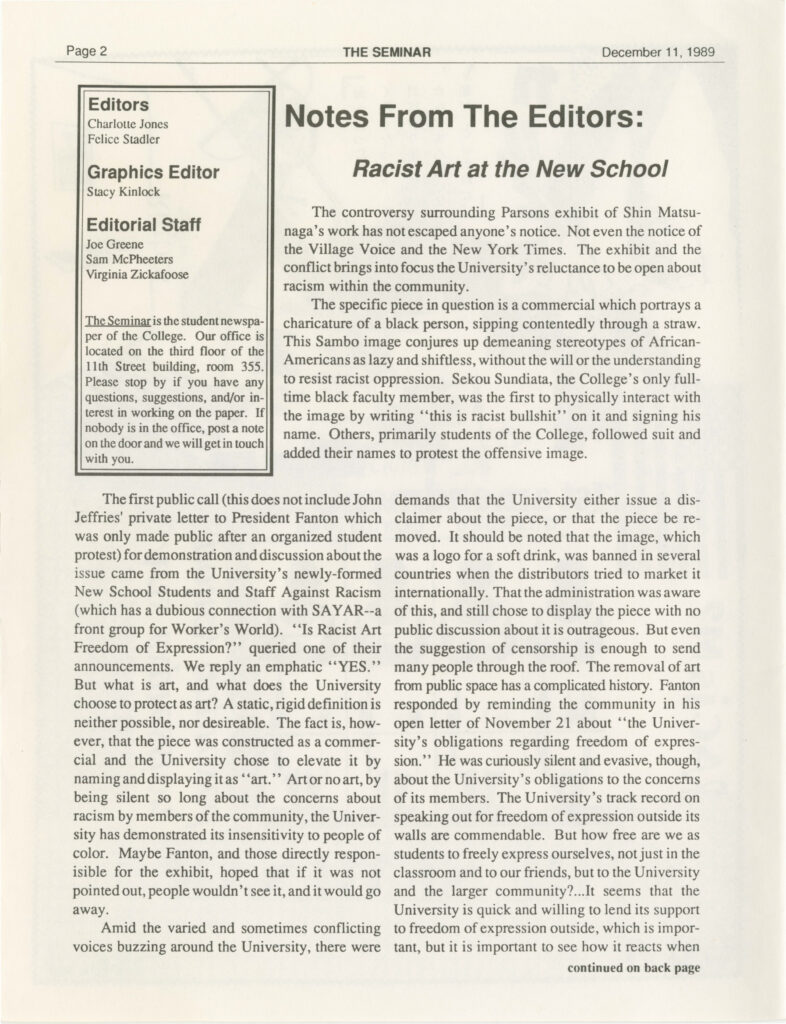

December 11

The Lang student magazine The Seminar includes several articles related to Sundiata’s defacement of the Calpis image. The cover art makes resonances with contemporary controversies clear. An editorial takes Fanton’s line.

December 14

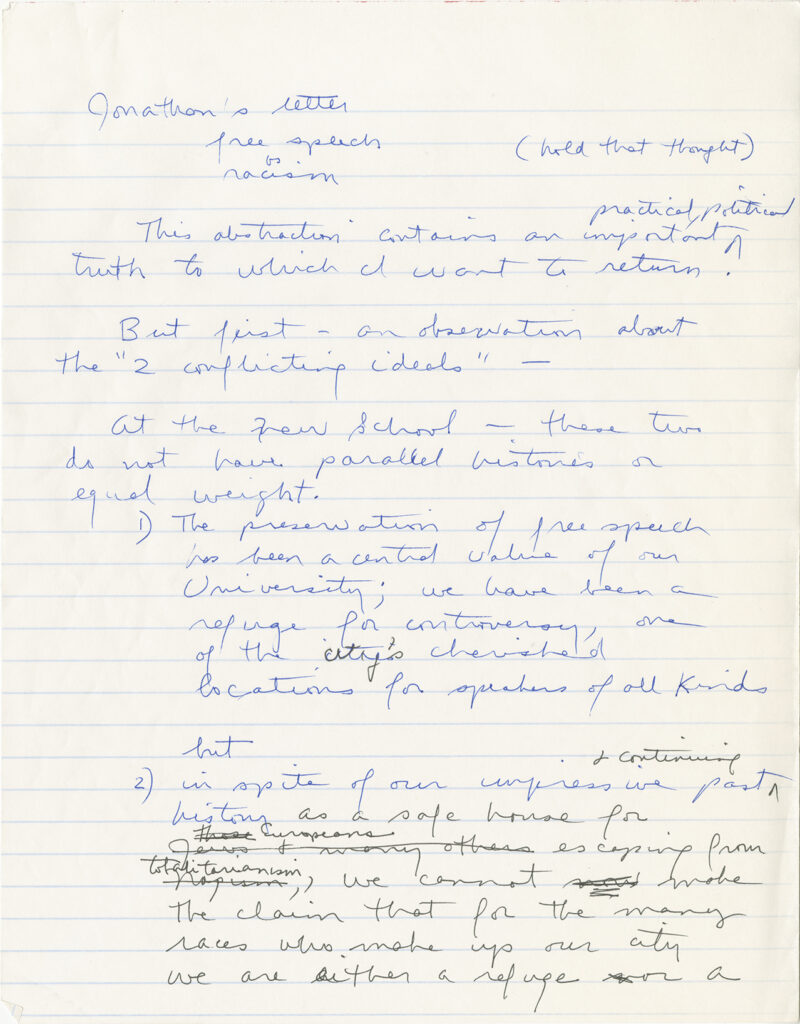

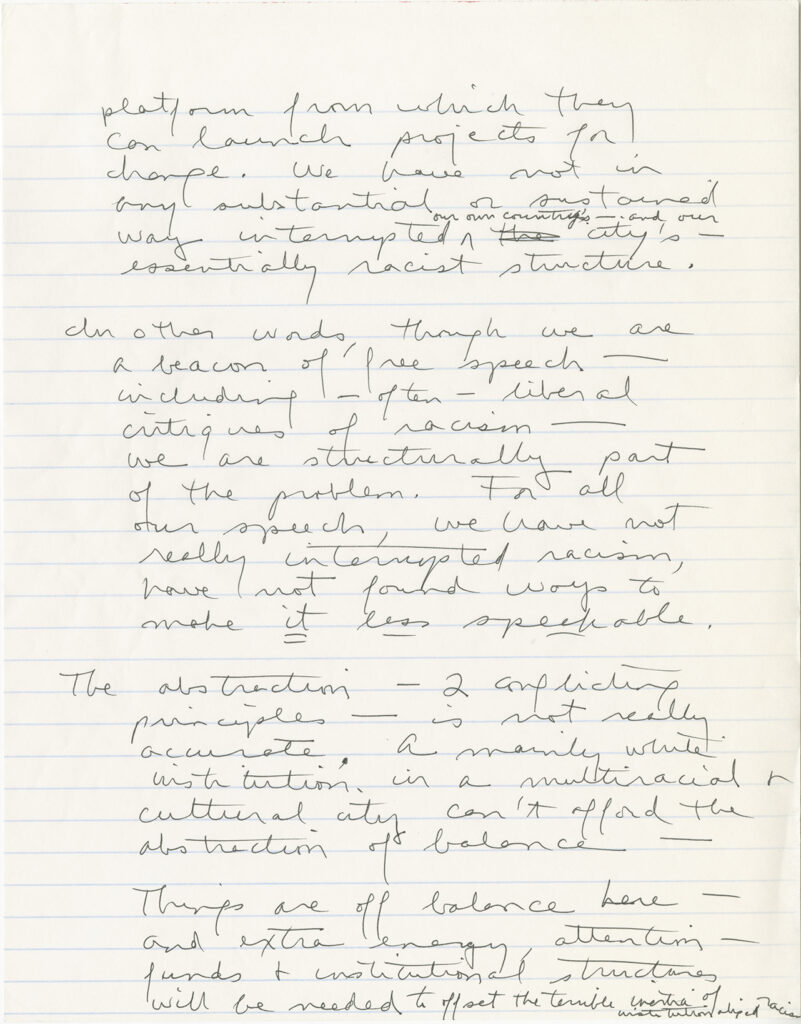

At a forum at Lang, Sundiata apparently asserts: “I didn’t deface it, I resisted it.” Snitow counters Fanton’s argument about the need to balance freedoms. A predominantly white institution in a mixed-race city “can’t afford the abstraction of balance,” Snitow argues. “These freedoms are simply not equally placed here at the New School.” Snitow goes on to express her support for Sundiata: “The New School is in Sekou’s debt for the shove his act has given to the inert mess which is any big institution.” She also calls for protesters to broaden their focus from the Matsunaga episode to structural questions, proposing a five-point agenda: “1) affirmative action plan with goals! 2) student recruitment with goals! 3) money to support tuition etc! 4) a curriculum of diverse courses, so that – at least some of the time – people can recognize themselves in what they read w/o having to perform endless acts of cultural translation! 5) a curriculum that helps people repair the ravages of high school.”

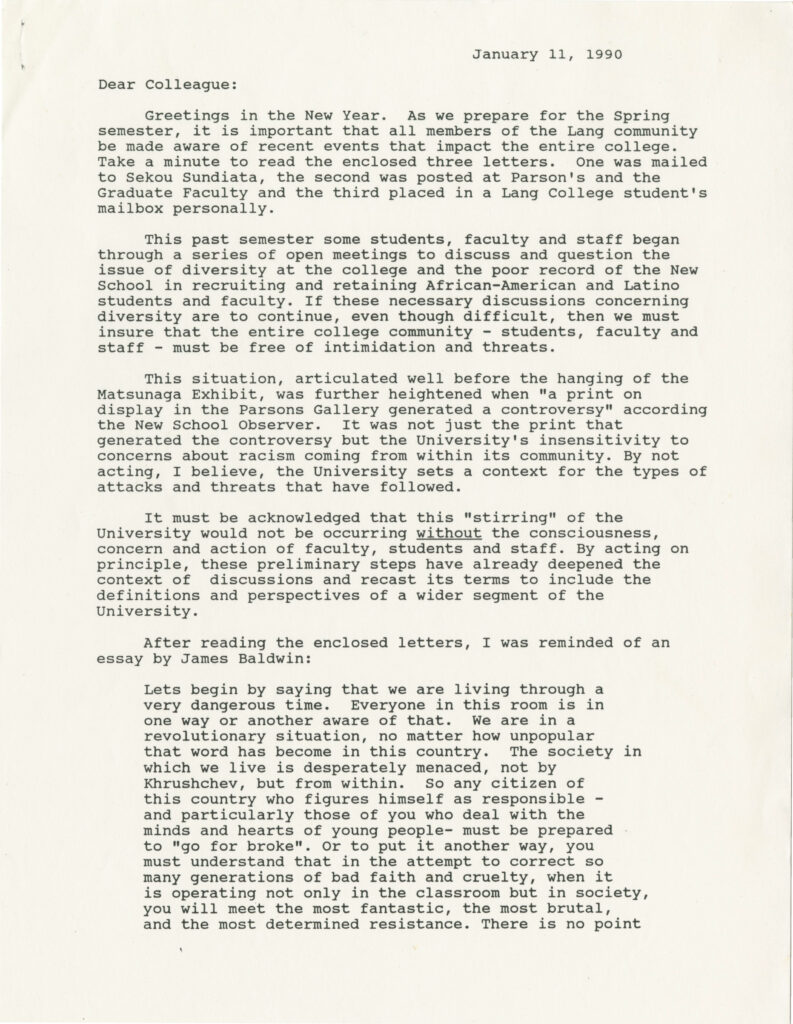

Two days before the end of the semester, hate mail is sent to Sundiata, distributed to Parsons faculty and the Graduate Faculty, and left in the mailbox of a student protester. In the new year, Tewksbury sends a letter to the Lang community with copies.

January 15 1990

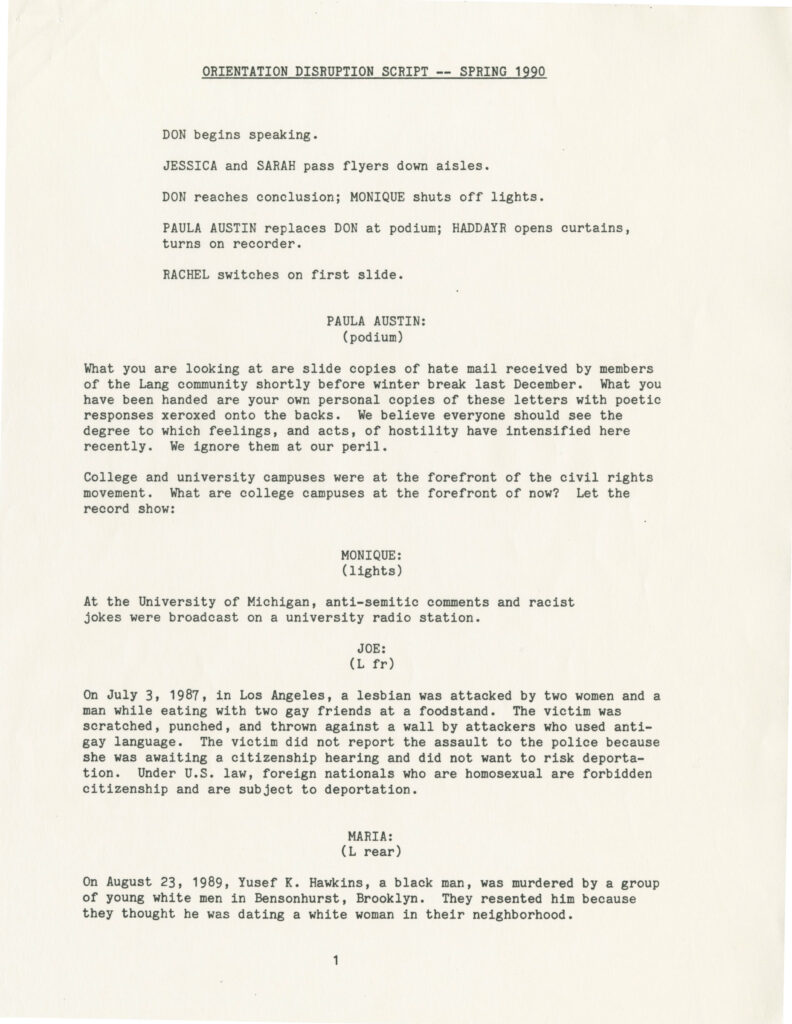

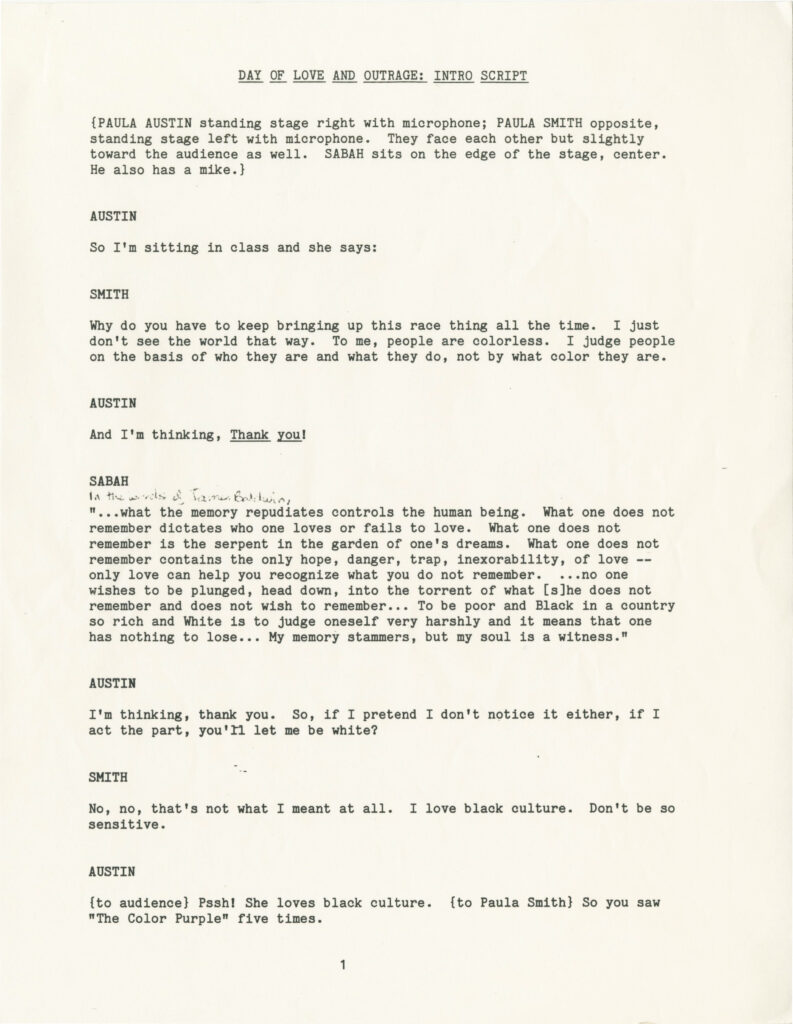

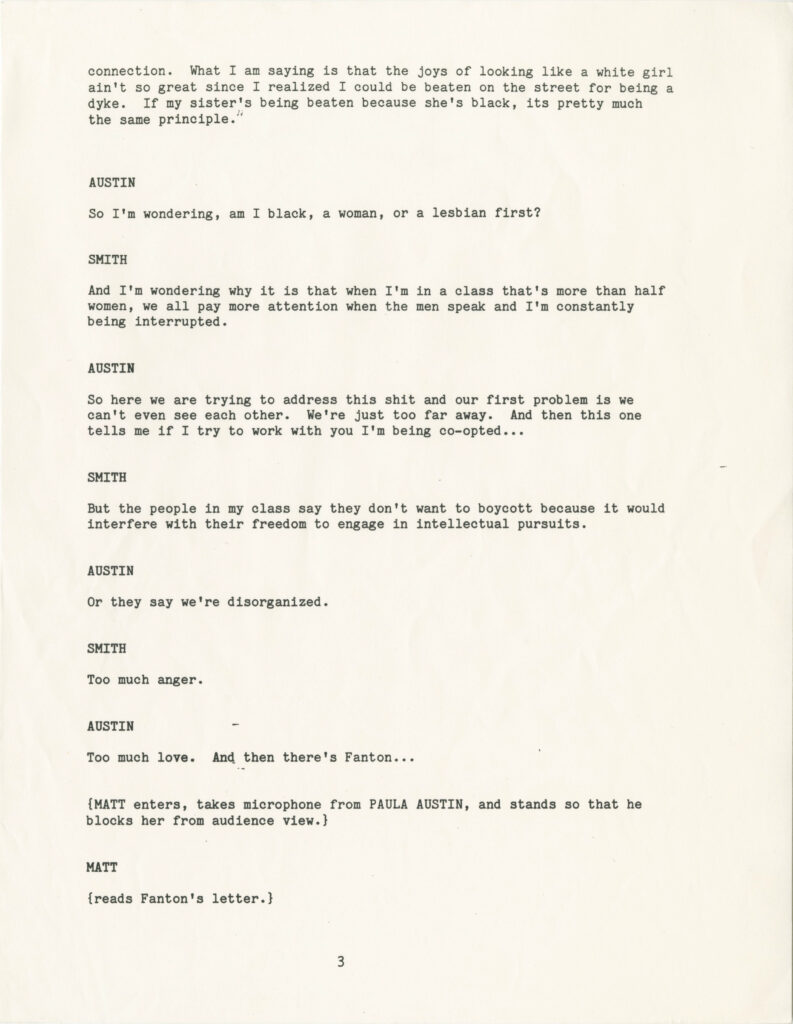

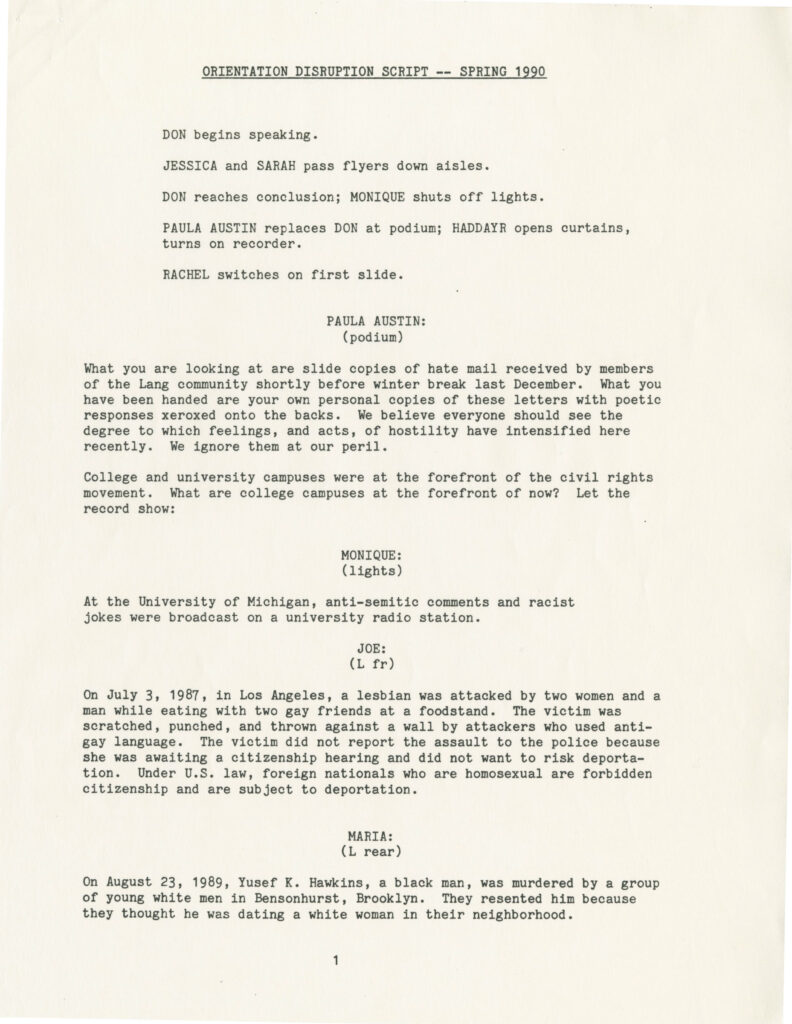

Students stage a “disruption” at Lang Student Orientation, placing the Calpis image and controversy in a global history of intolerance and violence. They call for their classmates to walk out of classes on Valentines Day, to make it a “working day on homophobia, sexism and racism.” The February 14th “Day of Love and Outrage” begins with a staging of intolerant claims within the classroom.

April 27

Matsunaga writes to Kuopus, expressing his regret about the “trouble.” He has learned “first-hand about the sensitivity of the American public to the racial issue, and as a result, I myself will be able to be more sensitive in the future.” In a published acccount a decade later, he again expresses his gratitude to Parsons for allowing the exhibit to run its course and draws lessons from the episode. “They concluded that regulating an art exhibit would be censoring artful expression.”

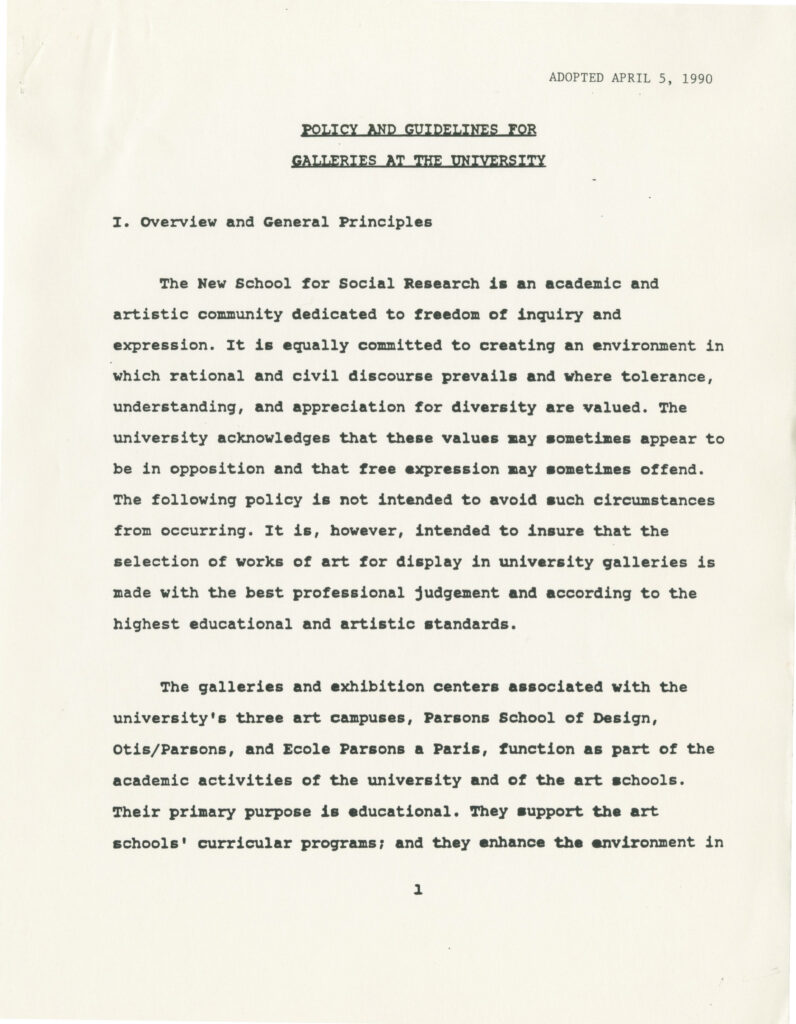

April 5

In response to a demand from Fanton, new guidelines are adopted that spell out the implications of the Statement on Artistic Freedom of Expression for exhibitions at the university. If the new policies are followed, an exhibition cannot be changed once opened. If “some members of the university community … take exception to the display of certain works of art,” however, the university has “a responsibility to be responsive” and “an obligation to facilitate … discussion when these circumstances arise.”

April 27, 1990.

May 1990

At Parsons Commencement, Fanton discusses the NEA’s anti-obscenity rider, using the Matsunaga controversy to call for ethical awareness on the part of artists and designers. “There can be no doubt that defacing the print was wrong, constituting as it did a form of censorship. … However, I believe it is also wrong for a designer or artist to employ images that gratuitously insult groups in our society on the basis of race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or any other personal characteristic.” Government must never “dictate or proscribe the content of art or design,” but it is “perfectly appropriate for you to ask yourselves questions such as whether you are using racist, sexist, or homophobic imagery.”

1990-1995

Faculty at Lang apply for and receive a grant from the Ford Foundation to reconceive the college’s curricular and extracurricular activities to “create diversity throughout the college community.” Pedagogy and student-faculty relationships are discussed, and sixteen new courses collectively developed. Sundiata’s work is prominent among faculty projects supported. The 1995 Final Report describes these initiatives and their “ripple effect” across the life of the college and the university.

February-March 1991

The Parsons Gallery revisits the question of racist stereotypes in popular culture and advertising, sponsoring the groundbreaking exhibition curated by Michele Washington and Fo Wilson, “Visual Perceptions: 22 African American Designers Challenge Modern Stereotypes.”

1994

Barbara Emerson is hired as Associate Provost in wake of million-dollar grant from Diamond Foundation for promoting diversity. Articulating principles of “awareness, appreciation, and alignment,” she leads efforts to diversify faculty, students and staff, and —with Sundiata’s help—puts together a major series of multicultural arts events around the city. She and some of her key staff leave in 2000 as a new presidency scales back the university’s commitment to diversity.