海へ行ったら

くろくなった.

目ばかり光って、

カルピスみたいな

顔だったと言われた.

Umi he ittara

Kuroku natta.

Me bakari hikatte

Calpis mitai na

Kao datta to iwareta.

Went to the seaside

And was tanned black.

My eyes alone sparkling,

Someone said my face

Looked like Calpis.

This poem was the caption for a 1987 ad for Calpis, a milk-based softdrink beloved of Japanese children since 1924. Kuroku natta, the standard way to describe one’s skin darkening with the sun, literally means “turned black.” The accompanying logo didn’t depict a Japanese person, however, but a caricature of an African American man from the age of minstrelsy and blackface, eyes rolled back in delight. Only in 1989 was the logo retired, under international pressure over racist imagery in Japanese popular and commercial culture.

In 1989, too, three months before the last bottles with the logo were produced, the Calpis logo appeared on the wall of an exhibition at the Parsons School of Design. Part of a show of the work of Japanese graphic designer Shin Matsunaga, it triggered a series of protests which ultimately forced a reckoning with The New School’s weak record on issues of race. The turmoil eventually led to revisions in exhibition policies as well as the presentation of a pioneering exhibition of work of African American designers taking on racist stereotypes at Parsons, a comprehensive student- and faculty-driven curricular reform at Eugene Lang College, and a university-wide effort to diversify the school community.

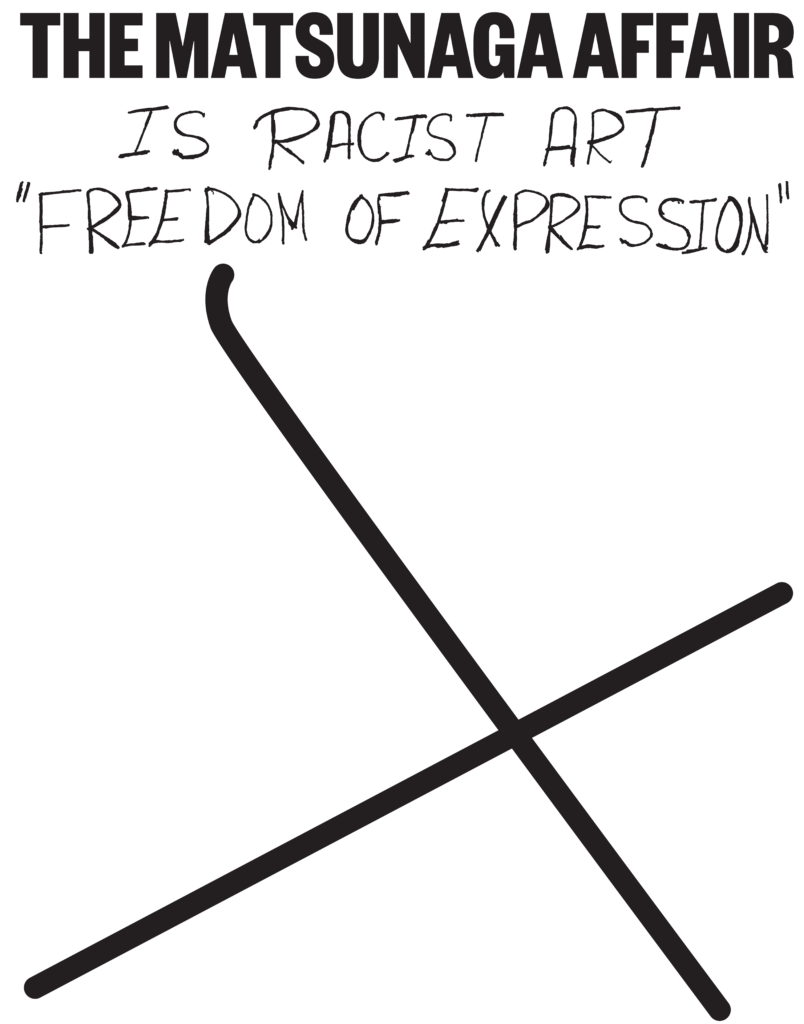

Galvanizing these reactions was an intervention in the work itself by spoken-word poet and Eugene Lang College faculty member Sekou Sundiata. A week before the exhibition was to come down, Sundiata drew an X in blue pen through the image and added his own caption:

This is racist bullshit

Then he signed his name: Sundiata. Other names soon appeared—and more intense controversy. Was Sundiata’s act vandalism, even censorship? Civil disobedience or, as he described it, “resistance”? Demands that the university take the offending image down or add a disclaimer to it were joined by calls of both condemnation and support of Sundiata’s action. The New School community found itself in a painful bind. Only weeks before the exhibition opened, the Trustees had approved a strong Statement on Freedom of Artistic Expression (it was the time of the Religious Right’s attacks on artistic freedom) and University President Jonathan Fanton had endorsed a “right to be free from intolerance.”

Perhaps The New School’s most widely reported episode of the “culture wars,” the “Matsunaga Affair” raises questions about the responsibilities of universities and their constituents to each other. How can spaces and communities of learning, creativity and engagement be structured and supported? How should issues of intolerance and difference beyond the university be engaged within it?